Intelligence plays a critical role during peacetime, particularly in informing policy decisions in areas such as diplomacy and crisis management. However, the demands and execution of intelligence processes undergo significant changes during wartime. This article explores the functional differences between policy intelligence and warfighting intelligence, emphasizing their implications for the training and education of professionals who engage with warfighting intelligence. It aims to supplement the perspective of Lars Borg and Marius Torgersen's call to re-energize warfighting intelligence (Borg & Torgersen, 2025).

Policy Intelligence

Policy intelligence involves gathering information to aid in strategic decision-making, facilitate diplomatic negotiations, and develop effective policies. This type of intelligence primarily focuses on identifying potential threats, understanding long-term trends, and analyzing the dynamics of sociopolitical environments.

Organizations responsible for policy intelligence are designed to provide independent, external assessments to the state's policy-making process, whether during peacetime or in times of crisis. In Western countries, foreign and security intelligence organizations are not directly integrated into the democratic policy-making structures and do not operate under the control of political parties. This separation is intended to prevent political bias and misuse of intelligence.

Instead, policy intelligence operates from an institutionally independent perspective, using its legal framework to support and inform political decision-making as needed. The process of policy-making does not require an integrated intelligence structure to produce formal policy.

Warfighting Intelligence

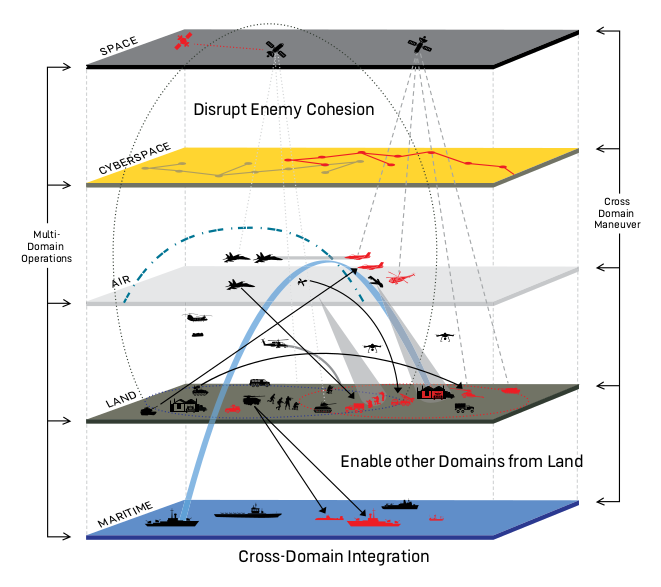

"Warfighting" refers to the methods, strategies, processes, and tactics used by military forces to conduct and manage combat operations effectively. Historically, it involves a specific set of functions that commanders combine, including planning, maneuvering, intelligence, logistics, communication, fire support, and command and control, to engage the enemy and achieve military objectives (Biçer, 2024; Lynch, 2023). Intelligence is a key component of warfighting, meaning that all intelligence cycles are integrated into decision-making processes at every command level. This integration includes detailed explanations of how the intelligence function relates to the other warfighting functions to combat the enemy effectively.

The warfighting intelligence function has its roots in the very first wars conducted by humans (Warner, 2006). Its inherent purpose is to provide commanders at all levels in the battlespace with a decision advantage relative to the enemy in terms of speed and precision in understanding the situation, known as the speed of relevance (Dransfield, 2020). The operations are governed by the Law of Intelligence-Driven Operations, which posits that all operations rely on human thought as a natural process. The only aspect that can be purposefully varied is the quality of intelligence that drives these operations. Even if a commander, lacking a professional intelligence organization, defines the situation, identifies threats, assesses enemy vulnerabilities, and develops a course of action for their units, the operation will still be intelligence-driven. Therefore, the production of warfighting intelligence and the individuals involved will significantly influence its quality. This quality, in turn, will logically be determined by the purposeful training and education of the personnel engaged in the operations.

The Peacetime Relationship

In peacetime, the relationship between policy intelligence structures and warfighting intelligence structures can be described as a "front-seat-back-seat" dynamic. In this arrangement, the national intelligence service takes the lead, while the military’s warfighting intelligence organization plays a supporting role. The warfighting intelligence organization provides support to policy intelligence when necessary and feasible. Additionally, the policy intelligence organization can assist with strategic collection or analytical assets during peacetime crisis military operations, or through international bilateral sources. However, it is important to note that military operational commands view this type of intelligence as a non-organic source of vetted intelligence. This means that the military must request such intelligence, as it cannot be mandated.

The relationship between national intelligence services and the military can be mutually supportive in both peacetime and during crises. In such cases, the national intelligence service may request military assistance for collection or analytical resources. Even when responsibilities are delegated, operational and tactical command generally remain under military control in most situations, even when conducting missions on behalf of the national intelligence service.

The Relationship In War

As war begins, the roles of intelligence change significantly. Warfighting intelligence takes precedence because it is specifically designed for combat and military operations against enemy forces. Meanwhile, policy intelligence becomes less central, although it still offers essential information for decision-making. Its effectiveness depends on the continuity and functionality of the relevant policy frameworks. If those structures dissipate due to the war (martial law, for example), policy intelligence may effectively vanish, with its personnel likely integrating into military intelligence structures until the war concludes.

With the onset of war, the overall intelligence shifts from advising policy in peace to functionally driving combat actions in war 24/7, actions that determine victory or defeat, life or death. Understanding the functional character of warfighting intelligence is essential for comprehending the distinct requirements for training and education of our intelligence professionals.

The Intelligence Warfighting Function

In modern warfare, military doctrine integrates warfighting functions across all involved commands, regardless of service, domain, or level of decision-making. Intelligence, as a critical warfighting function, has its sub-doctrine that outlines how the intelligence process works in conjunction with Command and other warfighting functions. This includes standard operating procedures tailored to various command levels, services, and domains (NATO, 2019, 2020). No Commander, Chief of Operations, or Battle Captain at any command level, service, or domain responsibility is expected to engage in combat without professional intelligence personnel.

This seamless integration of intelligence into operational planning is essential, as each warfighting entity—a company, brigade, ship, fleet, squadron, wing, task force, component command, or joint command—has its respective decision-making to conduct, whether it's for their small corner of a battlespace or the larger theatre of war as a whole. Each Commander relies on their intelligence cycle, tailored explicitly with sensors and analysts for their situation, to drive the planning and execution of operations for their area of responsibility.

The goal of every intelligence cycle in a theater is the same: to produce timely and actionable intelligence that enhances situational awareness and aids decision-making in dynamic combat environments. This capability provides commanders with a decision advantage over enemy forces (Dransfield, 2020). Whether that advantage stems from speed, precision, or a combination of both. Achieving a decision advantage translates into initiative, and seizing and maintaining this advantage is crucial for winning battles and wars.

Identifying threats is a crucial aspect of the warfighting intelligence workload, similar to policy intelligence. However, unlike policy intelligence, each intelligence cycle in a theater conducts threat assessments specifically tailored to the service, domain, command level, and current situation regarding the enemy. The time and accuracy with which these assessments are carried out directly influence the actions that will be taken. In contrast to policy intelligence, warfighting intelligence not only focuses on identifying threats but also emphasizes integrating and mitigating threats into planning and supporting real-time actions based on those assessments.

Threat intelligence in warfare brings an unprecedented sense of urgency that is typically absent in traditional policy intelligence work. This urgency is often felt personally, as the speed and accuracy of intelligence production can significantly impact survival in their specific area of operations. For instance, a daily update on the threat posed by known enemy man-portable air defense systems within your 50-square-kilometer area may seem irrelevant to the 100,000 personnel in the larger theater. However, for the smaller operational zone, this information is critical for planning airlift operations of the battalion and can mean the difference between life and death.

The urgency of war can escalate rapidly, where speed and precision ultimately determine the strategic outcome. Timely assessment of an impending major enemy offensive—derived from the collection and validation of hundreds of multi-sensor, multi-domain, and multi-service reports over several weeks—can mean the difference between victory and defeat.

The issue of time and chaos, as highlighted by Lars Borg and Marius Torgersen in their article, is a significant contrasting factor between policy intelligence and warfighting intelligence. This distinction explains the necessity of detailed doctrine, which encompasses standard operating instructions and procedures. For instance, it specifies which documents should be open on the current intelligence officer's computer screen in the tactical control center. This is where real-time management of an ongoing operation or battle takes place, and the current intelligence officer is ready to advise the acting Battle Captain as the chaos ensues.

Winning the war cannot rely solely on the prompt identification and mitigation of threats. A significant divide arises between policy intelligence and warfighting intelligence, particularly due to an additional intelligence workload that is typically not applicable to policy intelligence: targeting. Warfighting intelligence must provide options for engaging the enemy, resulting in a significant intelligence workload. It is essential to identify, disrupt, degrade, and destroy the enemy's warfighting structures, systems, and functions (Ducheine, Schmitt & Osinga, 2016; NATO, 2019; Pratzner, 2016). Targeting intelligence must systematically identify, collect, prioritize, engage, and assess the outcomes of targeting the enemy. This process requires continuous, round-the-clock urgency and needs to operate at the speed of relevance, as enemy intelligence organizations are actively working to disrupt, degrade, and destroy your operational capability.

Implications for Intelligence Education and Training

Warfighting intelligence represents a distinct mindset that differs significantly from peacetime policy intelligence. It is crucial to recognize the critical contextual and functional differences between these two areas, as they must influence the training and education of intelligence professionals. Currently, the peacetime intelligence community places a strong emphasis on policy intelligence in terms of training, education, and research. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a dedicated warfighting intelligence community that focuses on harnessing the synergies of practice, education, training, and research, and to create an environment that fosters its growth and development.

We need to establish the fundamental principles that will guide our warfighting intelligence professionals in their learning and practice. These principles will shape a training and educational environment that responds continuously to changes in technology, organization, and doctrine, striving to be as close to real-time as possible. The following list is not comprehensive, but it aims to highlight elements that encourage ongoing learning and adaptability, allowing our intelligence professionals to thrive in a future operating environment characterized by rapid innovation and the need for organizational warfighting agility (Mitchell et al., 2014; TRADOC 525-92, 2019).

Focus on tactical skills: Military intelligence professionals must develop tactical skills to analyze and respond to intelligence in real-time. Training focuses on scenario-based exercises, real-world missions, and the ability to think creatively and adaptively. We have entered an era of complex, multi-domain threat management and targeting, which requires a solid foundation in theories such as basic scientific principles, critical thinking, design thinking, and systems theory. (Clark & Mitchell, 2016). It is essential to recognize the role of your innovation cycle in the battlespace compared to that of the enemy. Achieving cognitive superiority at the tactical level is a crucial goal (Paulauskas, 2024).

Technological Proficiency: As technology increasingly shapes military operations, intelligence training is now centered on advanced technologies such as drones, cyber capabilities, artificial intelligence (AI), and sophisticated analytical tools. These tools are essential for effectively collecting and processing large amounts of data. In an era characterized by emerging disruptive technologies and multi-domain operations, it is crucial to continually evaluate whether the interplay between technology, organization, and doctrine achieves the desired outcomes (Topor, 2024). The presence of algorithmic coders in frontline intelligence units, capable of refining AI programming and drone sensor modules, should no longer be considered a concept straight out of science fiction.

Collaboration with Military Units: Military intelligence professionals, unlike their peacetime counterparts, are specifically trained to collaborate closely with combat units. This integration is crucial for ensuring that intelligence is both actionable and relevant to ongoing operations. It fosters routine and cross-functional experiences that significantly ease the transition from peacetime intelligence training to actual combat. It should come as no surprise that the principle of "train as you fight" also applies to the intelligence warfighting function.

Mission-Driven Education: Military intelligence professionals should receive education that includes extensive simulations and war games designed to replicate real operational conditions. This type of training is essential for personnel to understand the implications of their intelligence decisions in live situations. In peacetime, it is the only effective way to gain the experience needed to develop the crucial ‘gut feeling.’ Allowing them to experience mistakes and failures in a controlled environment, where simulated damage occurs, can be invaluable for their development (Lynch, 2023).

Crisis Management: Experienced intelligence officers in active battle operations will attest that even the most carefully planned operations can quickly become chaotic. Warfighting intelligence training should encompass crisis management and adaptability to equip personnel for the unpredictability of war planning, allowing them to pivot swiftly as circumstances change (Biçer, 2024). Fostering personal agility also enhances the resilience of the entire organization. Therefore, we do need "chaos pilots."

Packing these principles into an enduring educational model will require greater cooperation and integration among warfighting theorists, practitioners, researchers, and educators, as well as the establishment of supporting structures.

Conclusions

To conclude, warfighting intelligence is specifically designed to drive military operations and ensure mission success across various battlespaces, rather than to support peacetime policy decision-making. It also aims to protect the lives of our personnel across various command levels, services, and domains in the chaos of war. Neglecting to recognize this vital distinction in the training and education of our intelligence personnel can expose functional weaknesses in our warfighting capabilities, which potential adversaries could exploit to undermine deterrence. In a worst-case scenario, if war were to break out, we might find ourselves relying on luck to survive long enough to navigate a steep learning curve within our military intelligence organization.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Biçer, R. (2024). NATO’s Warfighting Capstone Concept: How Able to Anticipate the Changing Character of War? Wschodnioznawstwo, 18, 177–192. https://doi.org/10.4467/20827695wsc.24.012.20627

Borg, L., & Torgersen, M. (2025, May 4). Fra kompleksitet til kampkraft: Behov for en revitalisert taktisk etterretningsutdanning. Strategem. https://www.stratagem.no/fra-kompleksitet-til-kampkraft-behov-for-en-revitalisert-taktisk-etterretningsutdanning/amp/

Clark, R. M., & Mitchell, W. L. (2016). Target-Centric Network Modeling: Case Studies in Analyzing Complex Intelligence Issues. CQ Press. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483395807

Dransfield, J. (2020, January 13). How Relevant is the Speed of Relevance?: Unity of Effort Towards Decision Superiority is Criritcal to Future U.S. https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2020/1/13/how-relevant-is-the-speed-of-relevance-unity-of-effort-towards-decision-superiority-is-critical-to-future-us-military-dominance

Ducheine, P. A. L., Schmitt, M.N., & Osinga, F. P. B. (2016). Targeting: The challenges of modern warfare. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-072-5

Lynch, C. (2023). War Fighting (pp. 88–116). Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/cornell/9781501773020.003.0005

Mitchell, W., Alberts, D., Bernier, F., Farrell, P., Pearce, P., & al, et. (2014). C2 Agility (RTO No. SAS-085 FINAL REPORT ON C2 AGILITY). NATO. http://www.dodccrp.org/sas-085/sas-085_report_final.pdf

NATO. (2019, February). Allied Joint Doctrine for the Conduct of Operations. NATO Standardization Office (NSO).

NATO. (2020). ALLIED JOINT DOCTRINE FOR INTELLIGENCE, COUNTER-INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY.

Paulauskas, K. (2024). Why cognitive superiority is an imperative. NATO REVIEW. https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2024/02/06/why-cognitive-superiority-is-an-imperative/index.html

Pratzner, R. (2016). The Current Targeting Process. In Targeting: The Challenges of Modern Warfare (pp. 77–97). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-072-5_4

Topor, S. (2024). The Future of Warfare in the Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity Context. Revista Academiei Forţelor Terestre, 29(2), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.2478/raft-2024-0024

TRADOC 525-92, U. A. (2019, October 7). The Operational Environment and the Changing Character of Warfare. Department of the Army TRADOC Pamphlet 525-92 Headquarters, United States Army Training and Doctrine Command. https://adminpubs.tradoc.army.mil/pamphlets/TP525-92.pdf

Warner, M. (2006). The divnie skein: Sun Tzu on Intelligence. Intelligence and National Security, 21(4), 483–492.