If insurgency and revolution are social movements that go beyond the law, then a good case can be made that the advent of digital media has had little impact on their nature and goals since they are invariably still the same, namely to change the status quo. Indeed, it is neither easier nor harder to change the status quo now than before because in the end people still need to be convinced to go beyond the law in the physical world, as it always has been done. Committing oneself to supporting an insurgency involves crossing a significant threshold due to the potential dangers this entails. As Engels noted: ‘never play with insurrection unless you are fully prepared to face the consequences of your play’[1]. This is still valid today, a timeless truth. A 2011 tweet written about Tahrir Square during the Egyptian ‘Arab Spring’ echoes black American writer Chester Himes’ 1944 essay on civil rights.[2] It further underlines the invariability of physical commitment in insurgency: ‘Martyrs [are] needed [to] create incidents. Incidents [are] needed [to] create revolutions. Revolutions [are] needed [to] create progress’[3].

However, digital media has transformed society and insurgency is a reflection of the society in which it exists[4]. Therefore, surely digital media has influenced insurgency. Indeed, the means available to an insurgent through digital media allows him or her to disseminate ideas far more quickly than before and to a wider audience than with only analogue media. This essay will therefore argue that digital media is merely a new vehicle for insurgency and revolution, but not a transformer.

First, the essay will define insurgency and delimit digital media. Second, it will examine with a series of arguments and counter-arguments how digital media gives insurgents the chance to circumvent state and/or mainstream media control of their communications, whilst on the other hand giving state surveillance potential of the same media platforms. Lastly, this essay will explore how machine learning and/or AI might be a disadvantage to insurgents in the discursive domain.

This essay will view insurgency and revolution in synonymous terms and define them, in accordance with Nelson Mandela’s description as social movements that go beyond the law.[5] The difference in classification lies in an individual’s perspective. Whilst strategic theorists may talk about insurgencies, political scientist instead speak of revolutions. Similarly, when states support another government against usurpers, they are fighting an insurgency, but when states rather back the rebels, they are supporting revolution. Nonetheless, the goal of insurgency and revolution remains the same, namely to change the status quo and often with violent means.

Digital media will be delimited as the means of communication that are encoded in machine-readable formats. These saw widespread adoption from the late 1970s marked by the adoption and proliferation of digital computers. The first digital media appeared in the early 1800s in the form of Charles Babbage’s engines, Ada Lovelace’s computer programs, and Jacquard’s looms. However, these breakthroughs did not have global repercussions until over a century later during the digital revolution. This event marked a shift from mechanical and analogous electronic technology to digital electronics and ushered in the Information Age.[6] Put simply, anything available on the internet constitutes some sort of digital media, which is easy to copy, store, share and modify.

This essay will also employ Matthew Reinbold’s expression of ‘tribes’[7]. A tribe consists of multiple individuals sharing the same ideas and goals which they pursue in order to understand and change their environment. It is a group with which one feels a sense of solidarity and community of interests, as social psychologist Henri Tajfel popularly dubbed it: an in-group.[8] During a 2010 Ignite Talk, Reinbold explains how digital media can ‘super-empower’ individuals who seek to change the world, similar to insurgents who want to change the status quo.[9]

Professor David Betz accurately sums up John Mackinlay’s thesis from his book The Insurgent Archipelago comparing Maoist insurgency, i.e. pre-digital media, with post-Maoism insurgency, i.e. with digital media:

Maoist insurgent objectives are national, whereas post-Maoist objectives are global; the population involved in Maoist insurgency is local and singular, whereas the multiple populations involved in post-Maoist insurgency are dispersed and unmanageable; therefore the centre of gravity in Maoist insurgency is local, whereas in post-Maoist insurgency it is multiple and possibly irrelevant; the all-important subversion process in Maoist insurgency is top-down, whereas in post-Maoist insurgency it is bottom-up; Maoist insurgent organization is vertical and structured, whereas in post-Maoism it is an unstructured network; and whereas Maoist insurgency takes place in a real and territorial context, the post-Maoist variant’s vital operational environment is virtual.[10]

These post-Maoist traits do not indicate a transformation in the insurgent’s goal of changing the status quo with unlawful methods, however, they do show how the means of insurgency transform with the society it reflects. McLuhan’s concept of ‘global village’ describes how the world has been contracted into a village by electric technology. In Understanding Media,he explains how human awareness and responsibility ‘for the Negro, the teenager and some other groups’, has consequently been heightened to an intense degree where ‘[t]hey can no longer be contained, in the political sense of limited association’ and that ‘[t]hey are now involved in our lives, as we in theirs, thanks to the electric media.’ [emphasis in original][11]It is the society McLuhan portrays, a consequence of digital media, that enables the post-Maoist traits summed up by Betz.

Global Reach

In present day society, digital media transcends time and space and allows the insurgent’s messages global reach at near instantaneous speed. The reach of an insurgent’s ideas has been limited to the means available to him throughout history. These have evolved over time and permit an incrementally wider propagation of messages. In antiquity, for example, this was through the range of horses or ships, in the middle ages and renaissance it was amongst other accessibility to a printing press, but it is only since the widespread use of computers that the reach has been global.

Comparably, during the 90s, mass media in the form of global televised broadcasting did permit certain insurgent groups to disseminate their message to a worldwide audience. Most famously, Black September’s 1972 Munich Massacre allowed a few Palestinian radicals to focus the world’s attention on their struggle with Israeli-occupied territories. However, once the hostage situation was underway, these insurgents had little control over their message or how the media used it. Countries sympathising with the hostages tended to emphasise the existential threat of international terrorism, itself a concept conceived by these events.[12] Conversely, those sympathising with the terrorists focused on the unfairness of the Palestinian situation after the Six Day and Yom Kippur wars.[13] The media, not the insurgents, were effectively in control of the narrative, and were free to alter or censor the broadcast to their liking. In comparison, digital media has permitted insurgents to control their message and tailor their communication to an intended target audience.

Arguably the first insurgents to use digital media in this manner are the armed Islamist groups in Northern Caucasus fighting for independence from Russia. Since the First Chechen war, the group’s ideologies and goals are explicitly formulated online, but their attacks against the Russian government are advertised to reveal its vulnerability, and Chechen fighters who die in combat are remembered in virtual mausoleums.[14] These measures made the Chechen insurgency attractive to other jihadists and increased the number of foreign fighters that chose to ally with them. A decade on, al-Qaeda adopted similar methods and presented high quality and polished products reflecting a professional organisation that can handle digital communication in the same manner as established media houses.[15] In the right hands, pirated software and online tutorials allow small groups to appear more competent and qualified than they might actually be, giving them a degree of legitimacy in the eyes of the tribes they target. Since then, this use of digital media has become the standard for multiple insurgent groups worldwide.

However, when all of these groups are adopting the same methods of reaching their tribes, they risk getting their message drowned out by competing groups with almost similar agendas. After all, aspiring jihadists have a sort of luxury of choice of whom they wish to affiliate with because their ideologies are so alike. This in turn leads to competition for attention, akin to how commercial brands occupy space in advertising in order to secure awareness for their product. For Islamist extremists, this means making their digital products more entertaining and accessible, well directed and edited, filmed in high definition and more. Recent videos from al-Shabaab feature amongst other multiple camera angles, story driven directing reminiscent of action movies, and subtitles in at least three languages, thanks to Google Translate.[16] An attack against the Somalian government forces now has to be planned both militarily and photographically in order to make an impact.

Another way of getting attention is exhibiting provoking scenes such as violent executions. Daesh might not be the first group to execute hostages on camera, but is arguably the most notorious one.[17] Their exhibition of increasingly grotesque ways of killing their prisoners is to some extent a race-to-the-bottom of explicit content caught on camera. Other groups have imitated them, but this has only provoked an escalation in the level of violence before death.

These attention-grabbing methods all rely on digital media, and certainly made an impact when they initially appeared. However, once the shock over the existence of such actions abates, world audiences seem desensitised and focus their attention elsewhere instead of giving in to the insurgent’s desire for attention. In addition, several states keep servers that disseminate such content on blocked blacklists, and media houses refrain from addressing such cases very explicitly. The wider public has either grown to ignore it, or cannot easily view it, thus limiting the reach of the insurgent’s message. Nonetheless, resilient individuals can still gain access to the latter’s content, through VPNs[18] for example, in their search for a tribe to which they could belong.

Finding like-minded persons is substantially easier this last decade thanks to digital media in the form of social networks. Amongst numerous experiments, University of Cambridge’s big-five personality algorithm ‘Apply Magic Sauce’ predicts Facebook and Twitter members’ psycho-demographic profile from digital footprints of their behaviour, and this with surprising accuracy.[19] This means that should you share a certain number of particular ‘likes’ with another member, the chance of him or her belonging to your tribe is significant. The man behind the 2011 Norway attacks, Anders Behring Breivik, diligently hoarded emails from Facebook users for the sole purpose of disseminating his manifesto before his terror attack at Utøya, and attracted widespread attention to himself and his ideas.[20] This self-proclaimed ‘Solo Martyr Cell’[21] can also be interpreted as an extreme variant of focoism, only possible due to digital media. However, finding your fellow tribe members does not necessarily translate into actions in the physical world. Breivik’s vanguardism has yet to manifest any substantial follow-up insurgencies among his tribe.[22]

Social networks allow people to show support for certain causes, however committing beyond the virtual domain remains exceptional and rare, so called ‘clicktivism’ or ‘slacktivism’.[23] These concepts illustrate the paradox between the ease of showing support for a cause online, for example by clicking ‘like/share/tweet’, and the threshold of physically engaging for the same cause. This means that a social movement can appear significant online, but be void of physical impact in practice.

Furthermore, states have developed tools to profile, track and flag online users based on their digital trail. Mass surveillance programs such as the US National Security Agency’s Prism, British Government Communications Headquarters’ Tempora, or the Russian Ministry of Communications’ SORM process the enormous amounts of daily data flowing through servers located within their territories. Since the largest internet companies originate from these countries, most notably ‘the big five’[24], the monitored information often covers the entire online world. All mails, chats, posts, as well as other internet communications are scanned and made searchable, and programmed algorithms predicate certain types of behaviour such as radicalisation or bomb making in order to detect terrorists or insurgents. Even though these measures were slow to develop, they have nonetheless severely upset the use of the virtual domain for insurgent groups and foiled many planned attacks. ‘Lone-wolves’, as in individual insurgents, seem harder to track, but their attacks have few lasting repercussions on society.

The networked nature of digital-age insurgencies triggered a reaction from governments who are gradually cooperating more internationally to combat them.[25] Sharing intelligence to piece together the puzzle that is an insurgent network and prevent new attacks has increased significantly since 9/11.[26] Even former enemies such as the US and Russia, or Saudi-Arabia and Israel, are helping each other prevent attacks by insurgents.[27]

Digital media gives insurgency global reach involving multiple and dispersed populations, thus enabling a bottom-up subversion of these targeted audiences. Nevertheless, governments, populations and media houses have adapted and limited their efficacy.

Yet, the latest decade has given rise to popular uprisings such as the 2010 ‘Arab Spring’, 2011 Occupy Wall Street or 2014 Euromaidan, that have all appeared and gained momentum more quickly than the governments anticipated. Digital media also benefits the insurgents because their message can spread near instantaneously.

Instant propagation

The speed at which an insurgent message can be propagated in a community is increased with digital media. Notably images, around which most of digital media is centred, can be captured and uploaded in an instant with smartphones. Neville Bolt argues that the violent image is the central strategic operating principle of contemporary insurgencies, striking at the heart of the information age.[28] Indeed, as the famous idiom affirms, ‘images speak a thousand words’, and skilled insurgents can craft situations in which their narrative is emphasized by images connecting with known historical events or harmonises with collective memories.[29]

During the social movements of the ‘Arab Spring’, latent grievances in the populations of Tunisia and Egypt erupted in mass protests against the governments. Protesters used their handheld smartphones to organise by transmitting intelligence on security forces trying to stop them and disseminating plans for rallies and actions of resistance. The same is true for the Occupy movement that could seamlessly concentrate and disperse more quickly than the government could react.[30] This is the ‘holy grail’ of military tacticians in practice: the weaker party resists the stronger by deciding and acting faster, aptly described by Col. John Boyd in his 1976 Patterns of Conflict lectures.[31] There, he coined the concept of OODA-loop (Observe-Orient-Decide-Act) claiming that acting quicker will make the opponents actions useless, cause confusion, lower morale and reduce his will to fight.

However, most of these movements were initially triggered by a very physical event, such as the self-immolation of street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi which catalysed the ‘Arab Spring’ in Tunisia or the death of Neda Agha-Soltan during the 2009 Iranian Election Protests. Crossing the threshold into insurrection still requires strong motivation through symbols such as martyrs, even though digital media can help disseminate these more quickly than ever before.

The speed of insurgency also disfavours political consolidation after revolutions. Asef Bayat argues that the ‘Arab Spring’ in Egypt may have happened too fast. Instead of creating actual change in the political system it ended up only reforming some parts of it because insurgent success was so sudden that the different parties never had time to formulate a political plan. Only the Muslim Brotherhood with their Freedom and Justice Party had a clear plan and won the initial elections, but they were promptly overthrown and banned. Bayat suggests that these short unsuccessful revolutions where there is little new and much old, are instead ‘refolutions’.[32]

The governments involved in these contemporary insurgencies also learned their lessons regarding digital media. The most basic measure taken was cutting off access to the internet, but this was overcome with external assistance from solidary groups such as Anonymous.[33] Other measures include mass surveillance described in the previous section or deliberate disinformation spread in the same manner as that of the insurgent.[34]

The advantage of global reach and dissemination speed gained from digital media have been beneficial to insurgent movements, however despite a slow start, governments have adapted. Those more advanced can also be said to have gained the upper hand over the insurgent’s use of digital media through systems of mass surveillance. China may be the nation that has come the farthest with its proposed Social Credit System for developing a national reputation system.

The Chinese government is increasing its resilience to insurgency by rewarding desired behaviour through gamification of society. The State Council is developing a ‘citizen score’ to gauge individual’s prospects for accessing everything from loans, social support, rent apartments, dating sites, and more.[35] Its official Planning Outline states that:

Accelerating the construction of a Social Credit System is an important basis for comprehensively implementing the scientific development view and building a harmonious Socialist society, it is an important method to perfect the Socialist market economy system, accelerating and innovating social governance, and it has an important significance for strengthening the sincerity consciousness of the members of society, forging a desirable credit environment, raising the overall competitiveness of the country and stimulating the development of society and the progress of civilization.[36]

China is thus using digital media to continue Mao’s project of mass subversion. By applying gamification to society, they play on the human motivation’s predisposition for gratification through repeated actions.[37] A similar system can be said to exist in the West in the form of the big Silicon Valley high-tech corporations, but in China’s case, the government is the central driving force. Despite the advantages of digital media, insurgents may find it increasingly difficult to motivate the population to rebel when even the smallest non-violent action could have strong repercussions in all aspects of their lives.

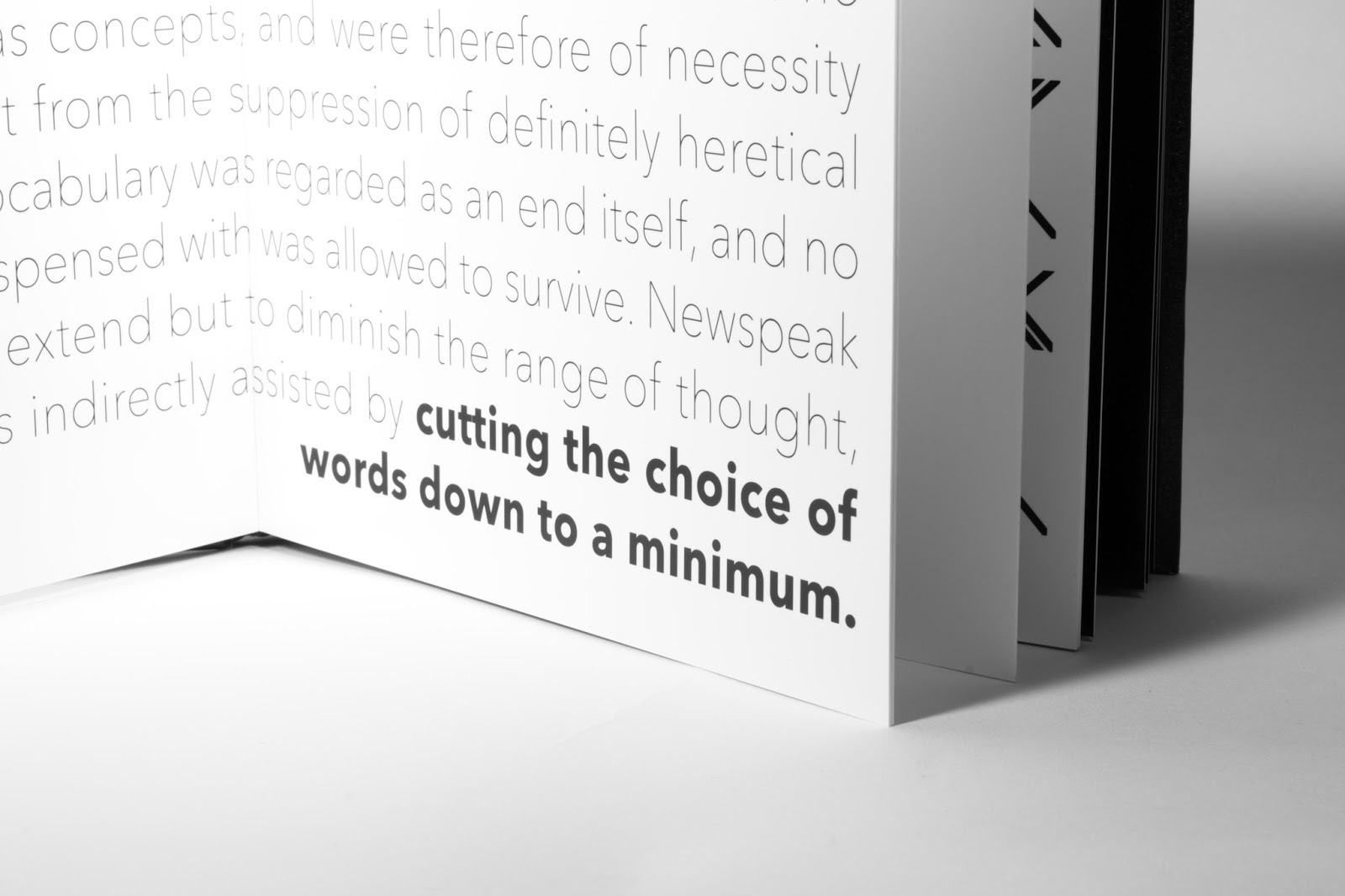

More worryingly is the potential repression of the philosophy of resistance that current AI research may make possible. Near future authority over words and vocabulary is currently outside insurgent’s or revolutionary’s control. Commercial actors might be unintentionally excluding certain ideas in their pursuit of building conversational AI through machine learning.

AI-developped Newspeak

The current AI and machine learning research programs and corporate competitions, of which a majority is being developed in English speaking countries or require using English as a language, require gigantic amounts of data, referred to as big data, for their machines to teach themselves.[38] This forceful application of the theory of evolution to artificial neural networks allows a program to rewrite itself according to its performance in a set number of tests. Just like a human gets better with practice, so does these machines. However, the amount of practice, i.e. the sheer amount of data analysed, eclipses human capabilities.

Arguably one of the most famous experiments is Alphabet Inc.'s Google DeepMind board gaming program AlphaGo.[39] This program taught itself how to win at the ancient Chinese game of Go by assimilating big data of human played Go games. After beating both the world ranked no. 2, Lee Sedol in 2016, and no.1, Ke Jie in 2017, the program has been further optimized by playing against itself and thus learning without datasets derived from human experts. This impressive technology is now findings its way onto more popular and everyday activities.

In 2013, Amazon released its intelligent personal assistant service Alexa. Just like Google’s Assistant and Apple’s Siri, users can use their voice to get Alexa to perform simple tasks like playing music, making to-do lists, setting alarms or controlling any smart devices connected to the network, such as lighting or thermostats. The obvious limitation lies in the restricted vocabulary and commands this assistant can understand, which in turn requiring the user to speak in an unnatural manner. However, in 2016, Amazon launched the Alexa Prize to further the field of conversational artificial intelligence. As the head of Amazon’s AI department stated, the demands are great because:

Human conversation requires the ability to understand the meaning of spoken language, relate that meaning to the context of the conversation, create a shared understanding and world view between the parties, model discourse and plan conversational moves, maintain semantic and logical coherence across turns, and to generate natural speech.[40]

To tackle this challenge, contestants were required to balance the amount of machine learning and human programing they would apply. In order to get enough big data to enable the former, participants resorted to two main sources. First, the internet where they processed the immense number of conversations between Reddit users. Second, after preliminary rounds in the competition, top programs were allowed live on Alexa for all its users to access and converse with.[41]

Insurgency ideas are omitted due to machine-learning algorithms using data that is already biased, incomplete, or flawed.[42] As illustrated by the AlphaGo example, machine learning seeks optimisation based on the big data it processes. Even though there exists a number of subreddits (topic specific channels on Reddit) on insurgent and revolutionary ideas, and some of them were amongst the most popular ones in 2017,[43] they dwarf compared to the number of mainstream subreddits. Moreover, despite radical overtones in the former, it usually is of a reformist rather than revolutionary character. Thus, the probability of encountering a conversation with Alexa on less discussed topics, such as insurgent ideas, is low and consequently not worth emphasizing in the optimisation process of the AI.

The cutting-edge research on conversational AI is thus not only based on the English language, but is also limited in terms of vocabulary to what is most prominently figured on Reddit or in everyday conversations with the average American Alexa user, which seems to exclude insurgent ideas.

It is possible to draw parallels to George Orwell’s depiction on how to control insurgent and revolutionary thoughts through control of language in Nineteen Eighty-Four.[44] Orwell’s protagonist works in the Ministry of Truth, Minitrue, which edits the dictionary of the official language Newspeak in order to reduce unorthodox political and social thought by eliminating the words needed to express them. Whilst Minitrue is deliberate, Amazon risks unconsciously/unintentionally doing the same thing as a consequence of its big data sources.

Current technology powerhouses are building their nascent technology based on sources that risk bias against unorthodox political and social thought. Just as the infrastructure of the web is in English, these companies’ actions today will fundamentally dictate the design and function of emerging technologies. Their research budgets dwarf those of competing states and the reach of their products is worldwide because they cater to a global audience.

In 1970, Gil Scott-Heron famously announced that ‘The revolution will not be televised’, pointing to the fact that real world physical commitment is paramount for an insurgency to succeed. Malcolm Gladwell writes in The New Yorker 40 years later that ‘The revolution will not be tweeted’[45], illustrating how digital media may have transformed the means of insurgency while little change has been made to its nature.

Photo: Grafitti from Cairo (unknown)

This essay was written at King's College London dept. of War Studies in 2017.

[1] (Engels and Marx, 1987, p.524)

[2] (Himes, 1944)

[3] Twitter user: jailanmagdy1; cited in (Bolt, 2013)

[4] (Betz, 2011, p.726)

[5] (Mandela, 1985)

[6] (Castells, 2010)

[7] (Reinbold, 2010, 2013)

[8] (Tajfel, 1974)

[9] Super empowerment is when individuals motivated by the same ideas are able to affect a disproportionately larger number of people; (Reinbold, 2013)

[10] (Betz, 2011, p.725; Mackinlay, 2009)

[11] (McLuhan and Gordon, 2003, p.6)

[12] (Bennet, 1973)

[13] (Reeve, 2001, p.147)

[14] (Mulvey, 2000)

[15] (Lynch, 2006; Brachman, 2010)

[16] (Bryden, 2015)

[17] (Euben, 2017; Marcellino et al., 2017)

[18] Virtual Private Network, a method for hiding a computer’s geographic location in order to access restricted parts of the internet

[19] (Tandera et al., 2017)

[20] (Hemmingby and Bjørgo, 2016)

[21] (Breivik, 2011, p.539)

[22] Foiled copycat attacks in UK and Czech Republic (Paterson, 2012; Mullin, 2015)

[23] (Halupka, 2018)

[24] Apple, Alphabet (Google), Microsoft, Facebook and Amazon

[25] (Jensen, 2016; Walsh, 2006)

[26] (Jones, 2007)

[27] (The Presidential Administration of Russia, 2017; Kramer, 2017)

[28] (Bolt, 2012)

[29] (Polletta, 1998)

[30] (Wasik, 2011)

[31] (Boyd, 1976)

[32] (Bayat, 2013)

[33] (Norton, 2011)

[34] (Hempel, 2016)

[35] (Hvistendahl, 2017)

[36] (Ström, 2017)

[37] (Whiston, 2013)

[38] (Krishnan, 2013)

[39] (Silver et al., 2016)

[40] (Ram, 2016)

[41] (Vlahos, 2018)

[42] (Noble, 2018)

[43] Actions to preserve Net Neutrality and protest against President Trump featured prominently in 2017 (‘blabyrinth’, 2017)

[44] (Orwell, 2013)

[45] (Gladwell, 2010)

Bibliography

- Bayat, A. (2013) Revolution in Bad Times. New Left Review. 80 (March-April), 47–60.

- Bennet, W. T. (1973) U.S. Initiatives in the United Nations to Combat International Terrorism. The International Lawyer. 7 (4), 752–760.

- Betz, D. (2011) Book Review: The insurgent archipelago: from Mao to Bin Laden. By John Mackinlay. Counterinsurgency. By David J. Kilcullen. International A airs. 87 (3), 725–726.

- ‘blabyrinth’ (2017) The Best of Reddit in 2017. Upvoted [online]. Available from: https://redditblog.com/2017/12/19/the-best-of-reddit-in-2017/ (Accessed 28 February 2018).

- Bolt, N. (2013) ‘Images of Dissent: Protest and the Limits of Social Networks’, in Mobilizing Dissent: Local Protest, Global Audience. World Politics Review. World Politics Review. p.

- Bolt, N. (2012) The violent image: insurgent propaganda and the new revolutionaries. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Boyd, C. J. (1976) Patterns of Conflict. 197.Brachman, J. (2010) Watching the watchers. Foreign Policy. (182), 60–67.

- Breivik, A. B. (2011) 2083 – A European Declaration of Independence. [online]. Available from: https://publicintelligence.net/anders-behring-breiviks-complete-manifesto-2083-a-european-declaration-of-independence/.

- Bryden, M. (2015) The Decline and Fall of al-Shabaab.

- Castells, M. (2010) The rise of the network society. The information age : economy, society, and culture v. 1. 2nd ed., with a new pref. Chichester, West Sussex ; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Engels, F. & Marx, K. (1987) ‘Letter to Marx, 16 January 1868’, in Collected Works. Internationale Marx-Engels-Stiftung. p.

- Euben, R. L. (2017) Spectacles of Sovereignty in Digital Time: ISIS Executions, Visual Rhetoric and Sovereign Power. Perspectives on Politics. [Online] 15 (04), 1007–1033.

- Gladwell, M. (2010) Small Change. The New Yorker [online]. Available from: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/10/04/small-change-malcolm-gladwell (Accessed 3 April 2018).

- Halupka, M. (2018) The legitimisation of clicktivism. Australian Journal of Political Science. [Online] 53 (1), 130–141.

- Hemmingby, C. & Bjørgo, T. (2016) The dynamics of a terrorist targeting process: Anders B. Breivik and the 22 July attacks in Norway.

- Hempel, J. (2016) Social Media Made the Arab Spring, But Couldn’t Save It[online]. Available from: https://www.wired.com/2016/01/social-media-made-the-arab-spring-but-couldnt-save-it/ (Accessed 4 April 2018).

- Himes, C. B. (1944) Negro Martyrs Are Needed. The Crisis. 159, 174.

- Hvistendahl, M. (2017) In China, a Three-Digit Score Could Dictate Your Place in Society | WIRED. WIRED 26 (01) p.48–59.

- Jensen, T. (2016) National Responses to Transnational Terrorism: Intelligence and Counterterrorism Provision. The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 60 (3), .

- Jones, C. (2007) Intelligence reform: The logic of information sharing. Intelligence and National Security. [Online] 22 (3), 384–401.

- Kramer, A. E. (2017) C.I.A. Helped Thwart Terrorist Attack in Russia, Kremlin Says. The New York Times. 17 December. [online]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/17/world/europe/putin-trump-cia-terrorism.html (Accessed 4 April 2018).

- Krishnan, K. (2013) ‘Big Data’, in Data warehousing in the age of big data. Morgan Kaufmann; Elsevier. pp. 1–124.

- Lynch, M. (2006) Al-Qaeda’s Media Strategies. The National Interest. 83 (Spring 2006), 50–56.

- Mackinlay, J. (2009) The insurgent archipelago: from Mao to bin Laden. London: Hurst.

- Mandela, N. (1985) Statement by Nelson Mandela read on his behalf by his daughter Zinzi at a UDF rRally to celebrate Archbishop Tutu receiving the Nobel Peace Prize. [online]. Available from: http://www.nelsonmandela.org/. [online]. Available from: http://www.nelsonmandela.org/.

- Marcellino, W. et al. (2017) Measuring the Popular Resonance of Daesh’s Propoganda. Journal of Strategic Security. [Online] 10 (1), 32–52.

- McLuhan, M. & Gordon, W. T. (2003) Understanding media: the extensions of man. Critical ed. Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press.

- Mullin, G. (2015) British ‘neo-Nazi’ alleged to have plotted mass cyanide terror attack [online]. Available from: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3076983/British-neo-Nazi-allegedly-planned-copycat-Anders-Breivik-terror-attack-bullied-child-having-ginger-hair.html (Accessed 4 April 2018).

- Mulvey, S. (2000) Analysis: Chechnya’s deadly martyrs [online]. Available from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/818697.stm (Accessed 20 February 2018).

- Noble, S. U. (2018) Algorithms of oppression: how search engines reinforce racism. New York: New York University Press.

- Norton, Q. (2011) Anonymous 101 Part Deux: Morals Triumph Over Lulz. [online]. Available from: https://www.wired.com/2011/12/anonymous-101-part-deux/ (Accessed 4 April 2018). [online]. Available from: https://www.wired.com/2011/12/anonymous-101-part-deux/ (Accessed 4 April 2018).

- Orwell, G. (2013) Nineteen eighty-four. London: Penguin Books : Great Orwell.

- Paterson, T. (2012) Breivik ‘supporter’ accused of plotting copycat attacks in Czech[online]. Available from: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/breivik-supporter-accused-of-plotting-copycat-attacks-in-czech-republic-8061623.html (Accessed 4 April 2018).

- Polletta, F. (1998) Contending Stories: Narrative in Social Movements. Qualitative Sociology. 21 (4), .

- Ram, A. (2016) Are You Up to the Challenge? Announcing the Alexa Prize: $2.5 Million to Advance Conversational Artificial Intelligence : Alexa Blogs[online]. Available from: https://developer.amazon.com/blogs/alexa/post/Tx221UQAWNUXON3/are-you-up-to-the-challenge-announcing-the-alexa-prize-2-5-million-to-advance-conversational-artificial-intelligence (Accessed 26 February 2018).

- Reeve, S. (2001) One day in September: the story of the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre, a government cover-up and a covert revenge mission. London: Faber and Faber.

- Reinbold, M. (2013) Networked Tribes, Super-Empowerment, and Resilient Systems[online]. Available from: https://matthewreinbold.com/2013/04/22/DecadeofPop-NetworkedTribes/ (Accessed 3 April 2018).

- Reinbold, M. (2010) Super-Empowerment, Networked Tribes, and the End of the World as We Know It. [online]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LmieSvccWfg.

- Silver, D. et al. (2016) Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature. [Online] 529 (7587), 484–489.

- Ström, T. E. (2017) Leviathan in Electric Sheep’s Clothing. Arena Magazine. (151), 11–14.

- Tajfel, H. (1974) Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information. [Online] 13 (2), 65–93.

- Tandera, T. et al. (2017) Personality Prediction System from Facebook Users. Procedia Computer Science. [Online] 116604–611.

- The Presidential Administration of Russia (2017) Telephone conversation with US President Donald Trump [online]. Available from: http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/56398 (Accessed 4 April 2018).

- Vlahos, J. (2018) Fighting Words. Wired 26 (3) p.72–79.

- Walsh, J. (2006) Intelligence-Sharing in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies. 44 (3), 625–643.

- Wasik, B. (2011) #Riot: Self-Organized, Hyper-Networked Revolts—Coming to a City Near You. WIRED 20 (01) p.76.

- Whiston, J. R. (2013) Gaming the Quantified Self. Surveillance & Society. 11 (1), 163–176.