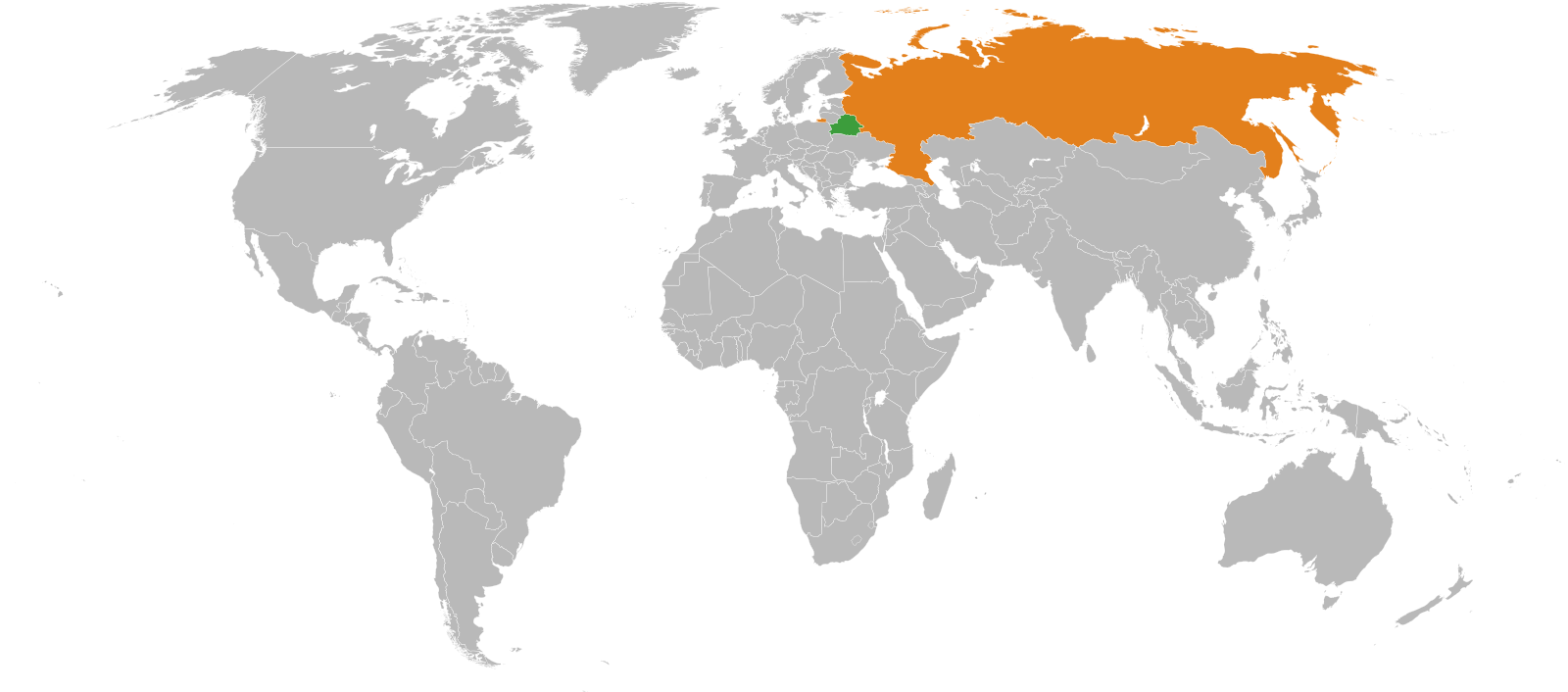

With the war going on in Ukraine, where Russia wants to be in control of Ukraine’s future, many international commentators, and most likely many government and intelligence services closely follow the developments in Belarus and the Russian-Belarusian relationship. Belarus is a large and resourceful county, and arguably – people and the culture are closely linked to that of Russia. Without doubt, Belarus is also perceived central to Russian security policies and strategies. By the end of the 1990s, Belarus and Russia signed a treaty, “The Union State Treaty”. The treaty has been less known, or at least largely been overlooked by most outsiders, and perhaps the two countries for many years. In fact, the relationship between the two countries have been questioned at several stages, as has the relationship between Russia and Ukraine. However, following some open disputes between Belarus and Russia over oil and gas supplies in 2018, Russia offered Lukashenko a simple choice: “Maintain energy subsidies for Minsk but only in exchange for intensified integration based on the long-forgotten Union State Treaty of 1999” (Shraibman, 2021). Ever since, the two countries have been discussing how to deepen the integration. The long serving president of Belarus, Lukashenko is perceived to be dependent on the Putin regime for trade, energy supplies, and perhaps his own survival as a leader in Belarus. The title of an article in the New York Times from 2023 paints the outside perspective well: “Belarus Is Fast Becoming a ‘Vassal State’ of Russia” (Valerie, 2023). In any case, there are great uncertainties about the Belarus regimes security and the country’s internal stability. In this essay, I examine the story of this increasingly important Union State Treaty of Russia and Belarus, including examining the state of affairs and main achievements of their relationship, as well as discussing some key challenges they have had – and perhaps still have, before finally discussing their known plans for the future.

The 25-year story

The Russian Federation and The Republic of Belarus became two independent states at the end of 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed. However, the two states have kept a close relationship and cooperated with each other since the dissolution. Belarus had early on an important position, where even Minsk became the designated administrative centre for the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in December 1991. As for economic integration, ambitions rose with establishment of the Eurasian Economic Community (EAEC or EurAsEC) in 2000, with the signing taking place in Astana, Kazakhstan (Shraibman, 2021). In 2015, the EurAsEC turned into the more well-known Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). Additionally, in 2002 Belarus became part of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) with several other post-soviet states, this reminds one about article five in NATO about collective security (Shraibman, 2021). We see that after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Belarus soon started to integrate back with the post-communist republics.

It is important to remember that Belarus also had a friendly, or at least open relationship with the West. Between 1995-99, Russia, with President Yeltsin, and Belarus, with still serving President Lukashenko, gradually developed their relationship through a series of treaties: first the “Treaty of Friendship, Good-Neighbourliness and Cooperation”, and the “Treaty on the Creation of the Community of Russia and Belarus”, which also included foreign policy, security, border protection and crime prevention through the formation of a so-called political and economic community. Finally, the “Treaty of the Establishment of a Community”, one of which is the establishment of the common economic space. The last treaty mentioned was to become the foundation of “The Union State Treaty”, signed in 1999 (Dean, 2021). When signing the treaty of 1997, President Lukashenko stated: “The main goal of the Union is to improve the lives of our citizens” (President of the Republic of Belarus, 1997). Lukashenko’s motivation for signing The Union State was to benefit economically. Integrating with the more resourceful neighbour would increase and stabilise the economy in Belarus. Also, from Russia’s perspective in the mid-1990s, Russia’s’ motivation was most likely of economic nature. In general, the commercial and economic interests of both states were most important in the mid-1990s. However, just by the late 1990s, other Russian political and economic leaders probably already saw potentials for expanding the nation’s sphere of influence in the former Soviet Union regions. As Putin came to power in 1999, ideas of establishing control and influence of the former Soviet Union states, as for instance Belarus, as well as Ukraine. Russia wanted to establish political and economic blocs around Russia, as the western countries had with NATO and the EU. Putin’s aspiration of having control over Belarus was probably only a short brick in this long goal to reunite the ‘near abroad’, a region united by common language, culture, and history (Ferris, 2022). From the beginning of the agreement in 1999 to the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Union State meant little in practice when it came to the relationship between Belarus and Russia. Belarus tried to balance trade and integration to the west and east, but western capitals got the impression of Lukashenko becoming more of an autocratic leader. The EU’s reaction to this was to put sanctions on Belarus for their lack of human rights and democracy (Shraibman, 2021). Both the sanctions on Belarus and the increasingly bitter relationship between Russia and Europe, contributed to leave Lukashenko with no other choice than to turn more towards Russia. Lukashenko was no longer a viable partner economically and geopolitically for the EU, and was therefore forced to integrate more with Russia, in order for him to continue holding onto power. After the war between Russia and Georgia in 2008, the EU again opened up to Belarus. Lukashenko exploited the standoff between Russia and the EU and managed to get financial help from the EU to win the election in 2010. However, the fairly good relationship between the EU and Belarus lasted only for a short time before the EU again sanctioned Belarus (Shraibman, 2021). The Belarusian balancing act continued, and after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, Belarus did not recognize Crimea as a part of Russia, but instead opened Minsk as a neutral place for negotiations. This again opened for better relations with the West, and trading possibilities. The relationship between Russia and Belarus became worse after 2014, when Belarus did not continue to integrate within the Union State. In response, Russia increased taxes on oil and gas exports, and openly threatened Belarus. However, later, in November 2021, Belarus abandoned its policy of nonrecognition of Russia's annexation of Crimea and stated that Crimea is 'legally Russian' (Przetacznik, 2023). In 2020, there was a new presidential election in Belarus. Lukashenko had just accused Russia of trying to drag Belarus into a Federation with Russia. After witnessing Russia in Georgia 2008 and Ukraine in 2014, Lukashenko realized how far Russia was willing to go to get back control over its ‘near abroad’. At the same time in 2020, there were huge political protests and demonstrations in Belarus following the presidential election.

The EU did not recognize Lukashenko as a president and once again put sanctions on Belarus. Another important event that distanced Belarus from the West, was the time Lukashenko forced an airplane from Greece to Lithuania to land in Belarus only to arrest the critical journalist Raman Pratasevich (Shraibman, 2021). Lukashenko then only had one option if he wanted to stay in power, and that was to turn to Russia for help to handle the chaotic situation in Belarus. There is no doubt that Russia wanted to support Lukashenko to keep him a pro-Russian leader, which again would make it less likely for Belarus to turn to the west and the EU. With an increasing polarization of the society in Belarus, Russia wanted more control in fear of more countries turning away from Russia. (Astapeni, 2021). Despite Lukashenko for several years feeling threatened by any deeper integration with Russia, something changed in 2021. It was a year of “crisis” in Belarus with threatening political forces against the regime. Following the crisis, the relationship became closer. Putin and Lukashenko then signed a new security doctrine, which changed Belarus’ status from a nuclear free country to a closely integrated security partner of Russia (Ferris, 2022). The Kremlin said that all nuclear weapons in Belarus would be controlled by Russia. This change was an important step for Putin’s future goal, says military and democracy experts. Opposition leader in Belarus, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, says that it will be hard to get rid of Russia’s strong presence in their country, even if it would come to a regime change (Hopkins, 2023).

Achievements and the union at present stage

In early 2022, Russia started their “special operation” in Ukraine, which is still ongoing. Belarus supported and stayed closely allied to Russia this time. When the invasion started, Belarus allowed Russian troops to train and preposition forces, before attacking Ukraine from the Belarusian territory. However, Lukashenko stated from the beginning of the war in Ukraine, that he would never send his own men in the war. Still, Emily Ferris wrote for RUSI that Belarusian troops would be sent to Ukraine “if necessary” (Ferris, 2022). Belarus’ involvement in the war in Ukraine has causes sanctions on Belarus from a huge part of the world (Jones, 2023). As of 2024, Belarus is still a military staging area for Russian forces. Officially, Belarus is still an independent state. However, in an article from Chatham House, Ryhor Astapeni describes how Lukashenko is letting Belarus become a ‘vassal state’ dominated by Russia, with its involvement in Ukraine. He also underlines the importance for western countries to become more active in and with Belarus if they want to influence the future for greater democracy and help Belarus escape the grip of Russia (Astapeni, 2023). Signing the treaty in 1999, Belarus and Russia had some shared goals such as creating a single economic and customs area, and a joint foreign and defense policies. The integration in trade, economy, connecting infrastructure and political stability has developed significantly since then. “In 2019, the Union State carried out twelve programs in space, military-technical, agricultural, and medical sectors, as well as microelectronics and hydrometeorology.” (President of the Republic of Belarus, 2024). Since Lukashenko in 2022 approved the Belarus-Russia draft treaty on harmonization of customs legislation and cooperation in customs matters, the two states have shared information and cooperated on customs control (President of the Republic of Belarus, 2023).

The citizens of Belarus and Russia are also now able to cross the borders between them without any passport or customs controls. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus states that citizens of both countries are equal when it comes to jobs, education, healthcare etc. Russia is the main trade partner of Belarus and the mutual trade between Belarus and Russia has only increased since the creation of the Union State. By 2022 mutual trade had increased by fifteen percent (Belarus MFA, 2024). They have recently managed to sign a three-year plan for the future of a common economic market, which is harmonizing the standards and regulations of a smoother trade relation (Информационно-англитический портал Союзного государства, 2024). Despite the complicated relationships and disagreements between the presidents Lukashenko and Putin, they have managed to keep political stability by gradually signing bilateral agreements within the Union State. As mentioned, Lukashenko’s popularity was very low in 2020. With help from Russia, Lukashenko maintained power and Belarus has been stable. Russia also benefited from or needed the close cooperation. Putin used the country actively during the war against Ukraine, and he uses it as a bulwark against NATO (Master, 2023). Through the Union State, Russia and Belarus are also coordinating air defense and security systems and have military training exercises. (Belarus MFA, 2024). The bilateral treaties of the late 1990s also included security, as discussed earlier. However, the security relationship between the two countries and within the Union State must be seen in conjunction with the wider Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). In addition to Russia and Belarus, the CSTO consists of Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. The CSTO’s original treaty had ambitions of a collective defense clause, not unlike NATO with its Article 5 (Dean, 2021). In conclusion, on the earlier achievements of the bilateral Union State Treaty, the legal provisions – particularly in the political and economic domains – have been mostly symbolic in nature. Few of the economic and political plans, such as the monetary union, the common energy market, or a joint constitution have come about. Integration in the military domain has been somewhat successful (Dean, 2021).

Challenges and problems

At large, there are two constant strains haunting the relationship and the various programs and plans for the union: First, the Belarusian leadership has a constant challenge with the internal, political stability of the country (Zogg, 2021); secondly, Russia has become gradually more ambitious and determined to control its neighboring countries.

Belarusian politics and society have fluctuated between stability and instability several times since the end of the Cold War, even though President Lukashenko has remained in power for a long time. The domestic legitimacy of Lukashenko’s regime has not been determined by elections since 1996 but has rather been based on a functioning social contract, financed by Russian subsidies, that provided relative well-being for Belarusian citizens in exchange for their political passivity. Since 2010, the regime has had challenges with internal stability following the long-term economic stagnation of the 2010s and the years since (Racz et.al., 2020). President Alexander Lukashenko, who has remained in power since 1994, has managed this largely through close ties to Russian presidents, mainly Putin since the millennium, and by controlling the elites in Belarus. Lukashenko’s control over the elites has been managed by two closely interconnected strands: “a pro-Russian stance and a monopoly on any contact with Moscow”. Lukashenko controls the decision-making process within Belarus, and he controls the elites’ trade and connections with Russia. This system has allowed him to remain the main allocator of trade. Simultaneously, the Belarusian ‘nomenklatura’ finds a great market in Russia, and in this way the Belarusian elite has largely supported Moscow politics. This again has given Lukashenko the support from the elites, as the sole pro-Russian politician in Belarus (Nizhnikau, 2022). The sanctions from Europe have also increased the economic dependence between the Belarusian ‘nomenklatura’ and Moscow, which again supports Lukashenko’s power position. Nizhnikau concludes that “economics has become the main instrument in Russian policy in Belarus, with emphasis being placed on the broadening of direct links between the economic elites”. The greatest crisis of government was perhaps in 2020-21, where mass political demonstrations and protests against President Lukashenko came as a result of unfair, rigged elections (Astapeni, 2022). The demonstrations began even before the 2020 presidential election. Demonstrations greatly intensified after the official election results declared Lukashenko as the winner.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, the main opponent of Lukashenko – after her politician husband was pulled out of the elections and sentenced to jail, strongly rejected the announced results. Following the protests after the election, Tsikhanouskaya had to escape the country for her own safety, and she was soon sentenced by a Minsk court to 15 years in absentia for treason, among other charges such as “conspiracy to seize power”. Her husband is serving an 18-year sentence, but unconfirmed rumors say that he has most likely died in prison (Loginova, 2023). According to Ryhor Nizhnikau, “the loyalty of the Belarusian ‘nomenklatura’ has always been one of the main buttresses of the Lukashenko regime”, but that unity was likely shaken by the mass protests and political crisis of 2020-21. Lukashenko was able to suppress dissent thanks to strong Russian support, but the Belarusian regime has never returned to its previous levels of solidarity (Nizhnikau, 2022). Most likely, Russia saw itself dependent on halting the democratic process in Belarus. According to Dunay and Herd, a “’democratic revolution’, if not economic liberalization, would cross Russia’s red lines: Belarus would no longer be a buffer and popular protest would have succeeded in enacting regime and system change” (Dunay and Hurd, 2020). As the main opposition politician of the 2020-21 “crisis”, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya said: “If Belarus is forgotten, Lukashenko can do whatever he wants.” Since she has fled to Lithuania, both she and many in the country’s opposition feel like the world has lost interest in Belarus (Loginova, 2023). Belarusian politics since the crisis have been reduced to being discussed only in the context of the war, or its dependence on Russia, according to Tsikhanouskaya. It now seems like President Lukashenko, with strong support from Russia, has managed to regain full control and stability of society. According to western journalist reporting on Belarus, human rights abuses in Belarus, which began long before 2020, continue unabated. The Guardian journalist Olga Loginova report that “there are now no active human rights organizations left in the country, more than 3,000 Belarusians have been prosecuted on charges of ‘extremism’ and just under 1,500 people in detention are considered political prisoners” (Loginova, 2023). Still, the internal stability of Belarus should be watched by Europe and NATO. Most likely, this is both a concern and opportunity for Moscow. One of the latest stories of Reuters hint at this continuing challenge: “Belarus investigates some twenty analysts over 'harming national security'” (Popeski and Singh, 2024).

As for the second, great challenge to a good relationship: Russia’s great power ambitions also define the future of the union. Russia is the greater power, in all aspects of this relationship with Belarus, and following Russian foreign policy is crucial. Alongside Ukraine, Belarus – in Russia’s perception – is crucially important as an extension of Russia’s own security space (Ferris, 2023). This essay will not go into the historic development of Russian foreign policy over the last two decades, but the scope will be limited to start from the current perspectives of the Russian state. Foreign minister Lavrov in current affairs normally sets the stage of his speeches by looking back to and portraying a narrative of how Russia and its neighbour countries have constantly been under pressure and have been exploited by the west since the fall of the Soviet Union. In fact, Putin, Lavrov and now most of the Russian leadership portray the fall of the Soviet Union as a “tragedy” (MID.RU, 2023). In an interview with RIA Novosti and Rossiya 24 TV in December 2023, Lavrov points out the story how The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) was created in Belovezhskaya Pushcha and in Almaty in December 1991, and how it today is under pressure because of the Ukrainian attempt to break this ideology of brotherhood and unity (MID.RU, 2023). Lavrov has for years argued the need for and Russian ambition of a "polycentric”, or true multipolar world order (TASS, 2021). Lavrov again links this to the development of a new world order, challenging western dominance. In Lavrov’s storytelling, this concept originates back to Yevgeny Primakov when Russia, India and China formed the RIC group, which again evolved into BRIC when Brazil joined the club and became BRICS with the addition of South Africa. Lavrov states that Russia will gradually move their efforts to introduce the BRICS culture into global politics (MID.RU, 2023). The view of Lavrov, which correlates to Russian policy: "Nowadays, when several Western countries seek to destroy the UN-centric international legal architecture and replace it with their own ‘rules-based order,’ bilateral dialogue on the global arena is particularly important. Moscow and Beijing are consistent supporters of the formation of a more fair, democratic and thus stable polycentric system of the world order <...> The very fact of Russian-Chinese convergence on this issue has had a stabilizing influence on the entire system of international relations," he said. (TASS (2), 2021). This understanding of the Russian state’s perspective on world order is crucially important to also be able to analyse and predict the future development of both the CIS at large, and The Union State of Russia and Belarus moving forward. With plans of moving forward with the Union with Belarus, and CIS, President Putin has approved a totally new and updated “Foreign Policy Concept” of the Russian Federation in 2023. On the foreign policy front, Putin stated they have a clear objective to develop the relations with those who are ready to work with Russia “on an equal, mutually beneficial and mutually respectful footing by engaging in a frank dialogue and talks for finding a balance of interests…”. He specifically noted what he called “our closest allies”: the Union State of Russia and Belarus and the Collective Security Treaty Organisation. In 2024, Russia leads the CIS. Russia plans to continue the useful projects launched in 2023. Putin also draws special attention to the International Russian Language Organisation, a CIS initiative proposed by Kazakhstan (RUSSIAEU.RU, 2024).

Plans moving forward

The cooperation between Belarus and Russia is still developing. Further plans for integration within the union especially have been discussed the last five years. As mentioned, Lukashenko was offered the “Medvedev’s ultimatum” in 2018 in which Belarus would get energy supplied from Russia only in exchange for intensified integration within the Union State. There is much to discuss, and compromise takes time when the goals of the two are different. Today, Russia and Belarus coordinate their foreign policy, and are continuing to improve law enforcement activities in order to prevent crimes, especially human and drug trafficking. They are also present on the western border to prevent illegal migration. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus highlights that their main priority now is to ensure equal rights for their citizens. With the treaty comes further development and integration in fields they are already cooperating in, as well as in new areas. They are continuing to develop cooperation in the fields of energy and industry, and both states support the strengthening of the post-Soviet area within other organizations such as the Eurasian Economic Union (Belarus MFA, 2024). At the end of 2023 the foreign ministers of Belarus and Russia signed a document on a three-year plan for the Union State, lasting until 2026. The Belarusian foreign minister said about this document: “This will make it possible to more closely correlate this document with other fundamental documents within the framework of the Union State” (Belarus Governmental Office, 2024). The Russian foreign minister Lavrov stated that: “Within the framework of the program, we also paid significant attention to building up cooperation in humanitarian matters with an emphasis on expanding the scientific, educational, and cultural space of the Union State” (Belarus Governmental Office, 2024). Establishing a common economic space has been presented as a major goal (Osborn, 2021). This is an advanced integration process and to improve this, Russia and Belarus are planning on implementing a road map (Belarus Presidential Office, 2024). Just recently, in February 2024, the industry ministers of Belarus and Russia met in Minsk and signed a concrete action plan for the three next years. The action plan would ensure that both follow the same industrial policy and regulations. Roadmap cooperation is a part of this signed document and is starting to develop in areas such as microelectronics, cooperation in machine tool building, joint work in agricultural and automotive engineering, and various specialized engineering tasks including developing equipment for airports. (Информационно-англитический портал Союзного государства, 2024).

Even though increased economic integration is high on the agenda for the way forward, there are still clear challenges that need to be dealt with. At a meeting in January 2023 hosted by Lukashenko, he pointed out that about 30% of the important activities discussed have not been implemented yet. He stated: “Yet, despite the implementation of most of the measures, Belarus has not yet seen any noticeable progress, primarily in the energy sector, manufacturing, or transport”. Lukashenko also pointed out efforts to implement programs to create common markets for gas, oil, and oil products (Belarus Presidential Office (2), 2023). Creating a common electricity market is a priority for the future of the Union State. In February 2024, Belarus and Russia discussed closer cooperation, including up to full integration of the gas, oil, and electricity market inside of the Union State. The Energy Minister of Belarus, Viktor Karankevich pointed out at a meeting in Vitebsk, Belarus that this draft on a future common electricity market is only the first step of the creation of such a market, as this draft already can be used to regulate electricity trade between authorized legal entities in the Union. The common energy market will ensure development and stability of energy systems, and an equal competitive environment. The energy ministers says that in the future, the common electricity market in the Union State will work to create a common electricity market of the Eurasian Economic Union. (BelTA, 2024).

Conclusion

Since the beginning of the Union in the 1990s, Russia and Belarus have had ambitions of, and tried to make their cooperation more efficient. Between 1995-1999, they gradually developed the relationship through a series of treaties, ending up with the “The Union State Treaty” of 1999. The treaty has not been very active for most of the time it has existed. Both countries have had great challenges in implementing plans for true economic cooperation. The article titled "The State of the Union: Military Success, Economic and Political Failure in the Russia-Belarus Union" from 2004 summarizes the early story well (Deyermond, 2004). The union has, however, grown more mature gradually over the last decade, not in the least following the 2021 "crisis" in their relationship. Today, both Russia and Belarus seem determined to expand their cooperation in all fields of foreign policy: for even greater integration of economic ties, loosing up on legal and customs challenges, and finally towards greater integration of the military and in the wider security domain. Belarus’ problems with internal stability, the elites, and Lukashenko’s dependencies on Russian support, currently put Russia in a dominant position. Belarus’ economy has benefited from the war in Ukraine, however their sovereignty is decreasing. It is hard to imagine that Belarus can say no to Russia in their aspirations for greater influence, as Lukashenko is more than ever dependent on Russia (Astapenia, 2023). No matter plans, the union and the cooperation between the two will most likely remain important, and troublesome – and should be followed closely.

LITERATURE

Astapeni, Ryhor, “Belarusians live in an increasingly divided country”, Chatham House, 2021. Downloaded 5 February 2024 from: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/10/belarusians-live-increasingly-divided-country

Astapeni, Ryhor, “Belarusians` views on the political”, Chatham House, 2022. Downloaded 5 February 2024 from: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2022/01/belarusians-views-political-crisis

Astapeni, Ryhor, “Rethinking Western polity towards Belarus”, Chatham House, 2023. Downloaded 5 February 2024 from: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/04/rethinking-western-policy-towards-belarus

Belarus Governmental Office, “Belarus, Russia sign program of concerted action in foreign policy”, 2024. Downloaded 15 February 2024 from: https://www.belarus.by/en/government/events/belarus-russia-sign-program-of-concerted-action-in-foreign-policy_i_165603.html

Belarus MFA, “Belarus and Russia”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus, 2024. Downloaded 14 February 2024 from: https://mfa.gov.by/en/bilateral/russia/

Belarus Presidential Office (2), “Meeting to discuss implementation of Union State sectoral programs”, President of the Republic of Belarus, 2023. Downloaded 23 February 2024 from: https://president.gov.by/en/events/soveshchanie-po-voprosam-vypolneniya-integracionnyh-programm-soyuznogo-gosudarstva-1673600105

Belarus Presidential Office, “The Republic of Belarus and the Russian Federation signed the Union State Treaty on 8 December 1999”, President of the Republic of Belarus, 2024. Downloaded 14 February 2024 form: https://president.gov.by/en/belarus/economics/economic-integration/union-state

Belta, “Belarus-Russia Union State common electricity market almost a reality”, Belta editorial, 2024. Downloaded 22 February 2024 from: https://eng.belta.by/economics/view/belarus-russia-union-state-common-electricity-market-almost-a-reality-156008-2024/

Deen, Bob, Barbara Roggeveen and Wouter Zweers, “An Ever closer Union?”, Clingendael Report, 4 August 2021. Downloaded 5 February 2024 from: https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/an-ever-closer-union.pdf

Deyermond, Ruth, "The State of the Union: Military Success, Economic and Political Failure in the Russia-Belarus Union", Europe-Asia Studies, Taylor & Francis, Ltd., Vol. 56, No. 8 (Dec., 2004), pp. 1191-1205.

Dunay, Pal and Graeme P. Herd, “Compounded Crisis in Belarus: Drivers, Dynamics, and Possible Outcomes?”, George c. Marchall, 16 November 2020. Downloaded 6 February 2024 from: https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/perspectives/compounded-crisis-belarus-drivers-dynamics-and-possible-outcomes-0

Ferris, Emily, “Belarus and Russia: Brothers in Arms?”, RUSI, 2022. Downloaded 1 February 2024 from: https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/belarus-and-russia-brothers-arms

Ferris, Emily, “Could Russia`s Reliance on Belarus be its Soft Underbelly?”, RUSI, 2023. Downloaded 1 February 2024 from: https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/emerging-insights/could-russias-reliance-belarus-be-its-soft-underbelly

Hopkins, Valerie, “Belarus Is Fast Becoming a ‘Vassal State’ of Russia, The New York Times, 2023. Downloaded 7 February 2024 from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/22/world/europe/belarus-russia-lukashenko.html

Jones, Gareth, ed., “Russia, Belarus ready to boost union state cooperation amid sanction, Reuters, 2023. Downloaded 30 January 2024 from: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russian-pm-says-moscow-minsk-keen-boost-union-state-cooperation-amid-sanctions-2022-03-14/

Loginova, Olga, “Belarus’s people are still resisting’: exiled leader calls for west’s support”, interview in Guardian, 23 August 2023. Downloaded 24 February 2024 from: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/aug/23/belarus-people-still-resisting-exiled-leader-sviatlana-tsikhanouskaya-calls-for-wests-support

Masters, Jonathan, “the Belarus-Russia Alliance: An Axis of Autocracy in Eastern Europe”, CFR, 2023. Downloaded 6 February 2024 from: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/belarus-russia-alliance-axis-autocracy-eastern-europe

MID.RU, “Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s interview with RIA Novosti and Rossiya 24 TV on current foreign policy issues, Moscow, December 28, 2023”, MID.RU. Downloaded 9 February 2024 from: https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1923676/

Nizhnikau, Ryhor, “The Growing Divide Between Lukashenko and the Belarusian Elite”, Carnegie, 2022. Downloaded 24 February 2024 from: https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/88443

Osborn, Andrew, Ed., “Russia and Belarus agree closer energy, economic integration”, Reuters, 2021. Downloaded 30 January 2024 from: https://www.reuters.com/world/russia-belarus-agree-closer-energy-economic-integration-2021-09-09/

Permanent Mission of the Russian Federation to the European Union editorial, “Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s statement and answers to media questions during a news conference on Russia’s foreign policy performance in 2023, Moscow, January 18, 2024”, RUSSIAEU.RU. Downloaded 11 February 2024 from: https://russiaeu.ru/en/news/foreign-minister-sergey-lavrovs-statement-and-answers-media-questions-during-news-conference

Popeski, Ronald and Kanishka Singh, “Belarus investigates some 20 analysts over 'harming national security’”, Reuters, 2024. Downloaded 23 February 2024 from: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/belarus-investigates-some-20-analysts-over-harming-national-security-2024-01-26/

President of the Republic of Belarus, Press Service, “Signing of the Union State Treaty”, 2 April 1997. Downloaded 10 February 2024 from: Официальный сайт | Официальный интернет-портал Президента Республики Беларусь (president.gov.by)

Przetacznik, Jacub, “Russia-Belarus military cooperation”, European Parliamentary Research Service, 2023. Downloaded 5 February 2024 from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2023/739348/EPRS_ATA(2023)739348_EN.pdf

Racz, Andras, “Four Scenarios for the Crisis in Belarus”, DGAP, 27 August 2020. Downloaded 6 February 2024 from: https://dgap.org/en/research/publications/four-scenarios-crisis-belarus

Shraibman, Artyon, “How to Build a Union: View of Societies and Elites in Russia and Belarus”, Clingendael Report August 2021. Downloaded 6 February 2024 from: https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2021/an-ever-closer-union/annex-1/

TASS editorial, “Russia, China see eye to eye on polycentric world order for global stabilization — Lavrov”, TASS, 1 June 2021. Downloaded 9 February 2024 from: https://tass.com/politics/1296517?utm_source=google.com&utm_medium=organic&utm_campaign=google.com&utm_referrer=google.com

TASS editorial, “Shift towards polycentric world system cannot be ignored, Lavrov says”, TASS, 23 JUL 2021. Downloaded 9 February 2024 from: https://tass.com/politics/1317095

Zogg, Benno, “Power and Paralysis: Stalement in Belarus”, RUSI, 2021. Downloaded 2 February 2024 from: https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/power-and-paralysis-stalemate-belarus

Информационно-англитический портал Союзного государства, «Belarus, Russia sign action plan in manufacturing for 2024-2026”, 2024. Downloaded 16 February 2024 from: https://soyuz.by/economics/belarus-russia-sign-action-plan-in-manufacturing-for-2024-2026

Photo: Defence Ministers of Russia and Belarus discussed joint activities for 2021/Wikimedia commons