Executive Summary: The Arctic is an arena for strategic competition. Developing a viable and comprehensive strategy is critical to maintain a competitive advantage and counter Russian and Chinese influence and malign activities. There are eight Arctic nations; Canada, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, United States, Russia, and Iceland. USSOCOM is in a unique position, with six of these eight Arctic countries represented in their headquarters with exchange or liaison officers assigned to the J3-International Division. This provides an exclusive capability and opportunity for USSOCOM and the U.S. Department of Defense to facilitate enhanced understanding of the situation and enable the development of an informed and integrated international special operations Arctic strategy.

The Arctic – An Area for Strategic Competition

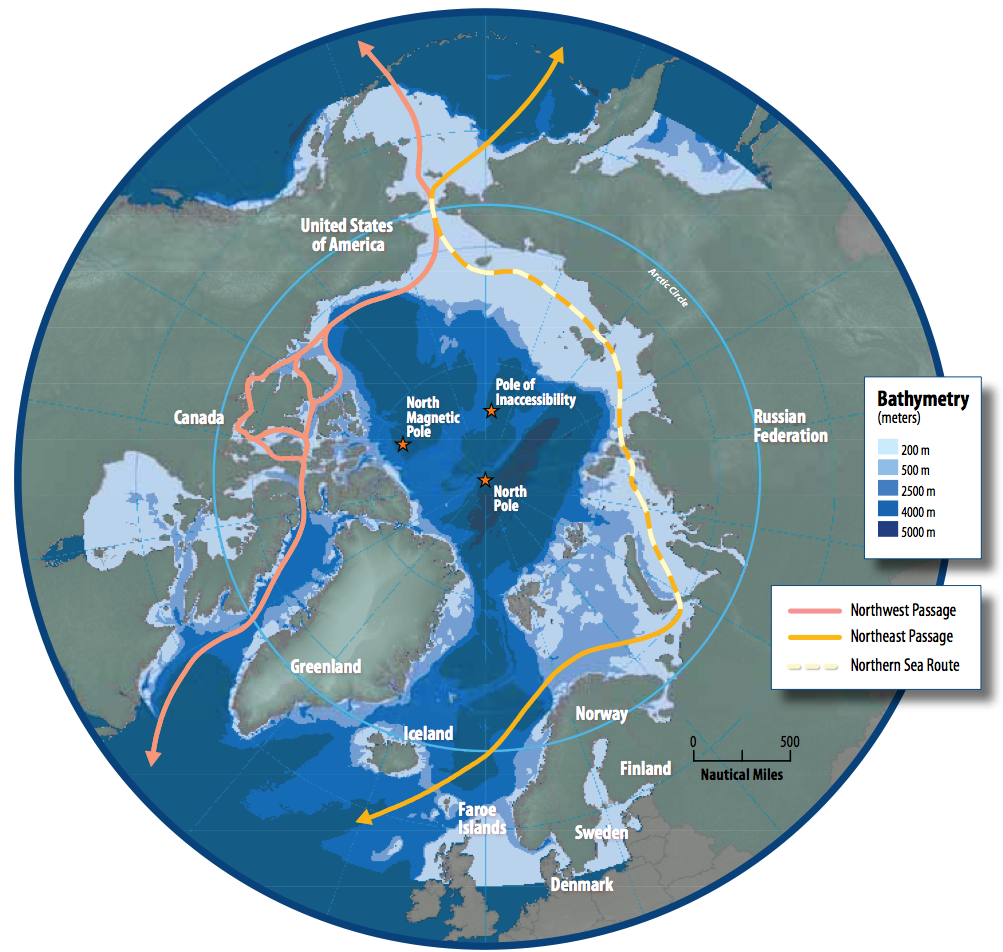

Military experts seem to agree that the Arctic is a rapidly growing arena for strategic competition. The polar ice is melting, creating new corridors for sea transportation, and opening opportunities for extended extraction of resources, such as seafood, oil, gas, and minerals. Historically, with significant national economic opportunities like those listed, security interests evolve and establishing a favorable stability soon follows as a priority. Both Russia and China acknowledge that the Arctic is an area of great strategic interest, and an area where they are willing to compete with comprehensive and coordinated means. Nations that do not deliberately dedicate their attention to this environment will be ceding a competitive advantage to those that will.

The Arctic presents unique challenges from an operational perspective. The remoteness and size of the region cannot be overstated. And despite the common perception of stable snow and ice, the environmental conditions can change significantly from month to month in the whole region. The sustainment of operations requires enhanced and tailored logistical capabilities. More simply put, it requires more support to accomplish less when compared to other operations, even in remote areas like Afghanistan. The harshness of the environment affects all variants of technology, and even basics like fuel, power (batteries), or the electro-magnetic spectrum will pose specific challenges. Standard equipment can not merely be deployed to this environment without modifications.

Simply developing and maintaining the required capabilities and expertise to effectively operate in the Arctic is an extremely complex and challenging task. Successfully competing in the Arctic is an entirely different endeavor. Effective competition requires situational understanding and persistent presence in the form of influencing or shaping activities. Potential activities could include joint and combined training exercises, civil-military operations, support to scientific research and expeditions, search and rescue operations, security and presence patrols, reconnaissance or intelligence operations, and operations intended to communicate strategic messages. The Arctic truly is a multidomain environment that requires a comprehensive approach to effectively compete and influence. Developing a deliberate strategy, comprised of appropriate activities as well as assessing their effectiveness, requires an understanding of the social, geopolitical, and environmental factors. Unless it is a singular priority, the scope and scale of effort required to effectively compete generally exceeds the capacity of any single nation.

The United States and the Arctic Partner Nations.

The Arctic is comprised of eight nations: The United States, Russia, Canada, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, and Iceland. Each of these nations maintains their own sovereign territory and strategic interests in the region. The potential effectiveness of a strategy for competition is reliant on the degree of integration with the Arctic allies. From the U.S. DoD perspective, the Arctic spans three different Geographic Combatant Commands (USNORTHCOM, USEUCOM and USINDOPACOM), each with their own unique requirements and equities. Additionally, although populations that live above the Arctic circle are sparse, each nation has their own unique indigenous populations that inhabit their territories and plays a key role in the region.

Russia

Russia understands the necessity for preparing its forces, equipment, tactics, techniques, procedures, and training for Arctic conditions. In 2020, Russia developed an Arctic strategy looking forward in a 15-year perspective, focused on controlling Arctic natural resources and the Northern Sea Route. Russia has heavily developed its military capabilities in the region. They benefit from their experiences in cold-weather training and have implemented the lessons learned from the numerous winter campaigns in their recent history. The Norwegian Intelligence Service (NIS) reported in its annual intelligence assessment that to support Russia's interests in the Arctic, the Northern (Russian) Fleet’s ability to conduct military operations has been strengthened in general, particularly for Arctic conditions.[i]

China

China continues to expand its influence inch by inch through a long-term strategic mindset, smart economic investments, advanced networks, diplomatic coercion, and other means. China has multiple interests in the Arctic. Utilizing the Northern Sea Route along the Russian coast, Chinese merchant ships can reduce the sailing-distance to European ports by thousands of nautical miles. China also sees the Arctic as a source of protein (fish) to its growing population and recognizes the vast amounts of natural resources, more specifically, gas, oil, and minerals, all of which are vital ingredients to China’s technology industry.

The Role of Special Operations in the Arctic

USSOCOM, in its role as a functional combatant command for U.S. special operations forces, operates in a manner similar to a service component. Much like the Army’s Arctic strategy, as articulated in the January 2021 Regaining the Arctic Dominance – The U.S. Army in the Arctic,[ii] ideally a SOF Arctic strategy would not only outline the environmental requirements, but also the potential operational requirement needed to support the Joint force concept for competition. More specifically, it is important that special operations capabilities remained linked to the Joint Forces capabilities and requirements and not purely based on what now seems to be traditional or legacy special operations activities. It would help inform readiness, training, force development and modernization efforts specific to special operations requirements.

In general terms, the likely contributions of special operations forces to a competition strategy would include a combination of exercises (that demonstrate capability and create presence), discrete steady state operational capabilities (such as civil-military operations, reconnaissance and intelligence operations, security patrols, etc.) and low visibility and contingency (special) operations (in response to aggression or conflict). Geographic Combatant Commands (GCCs) and the Theater Special Operations Commands (TSOCs) need to share a common perspective on exactly what types of special operations SOF-units are prepared to conduct and contribute with in terms of the Arctic (and how it actually relates to the GCCs’ requirements). Achieving this requires more than understanding joint and service doctrine. It requires a synchronization of campaign design and objectives, validated by experimentation and war-gaming with the different unit’s capabilities. This ensures capabilities and concepts to continue to evolve and remain relevant. This type of integrated approach would also better inform senior military decision-makers of the options available “for competition,” as well prepare the special operations forces units to conduct the required special operations.

The need for a USSOCOM Arctic Strategy

USSOCOM is in a unique position to synthesize the GCCs’ operational concepts and requirements (facilitated by the three TSOCs with Arctic responsibilities) with the readiness, training and equipping of their subordinate special operations forces, under the daily command of its service components (USASOC, NAVSPECWARCOM, AFSOC and MARSOC). This would ensure that special operations forces’ development and modernization efforts remain grounded in evolving operational concepts and requirements (and not based on the assumption of legacy requirements and nostalgic perceptions of what SOF represents).

Additionally, the USSOCOM maintains a unique global network of SOF partnerships. Within the USSOCOM headquarters are twenty-eight allied special operations exchange officers and liaison officers (assigned to the J3-International Division). Among these are international personnel from five Arctic nations in addition to the U.S: Canada, Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Denmark. In addition, there are numerous other partners with equities related to the Arctic within the same headquarters. This represents a relevant and unique capability if we utilize it in the right manner. This unique capability could enable USSOCOM to integrate allied SOF partners’ expertise and operational efforts into U.S.-centric theater plans, and thereby help generate both a national and an integrated multinational strategy for special operations forces in the Arctic. Harnessing this allied expertise and participation would also ensure that U.S. plans are based on a comprehensive perspective and have a multi-domain, holistic approach to the region.

Such an integrated strategy could significantly enhance the U.S. Joint Staff and GCCs’ plans for competition in the Arctic by synchronizing various disparate efforts resulting in a more comprehensive and holistic approach compared to what we experience today.

Foto: Forsvaret

About the authors:

Mark Grdovic is currently the Senior International SOF advisor within the U.S. Special Operations Command Headquarters J3-International Division. In 2012 he retired as a Special Forces LTC from the U.S. Army. Since his retirement from active service, he has served in a variety of positions, including as a strategic planner at U.S. CENTCOM, an operations advisor in SOCCENT and Adjunct Faculty member at the U.S. Special Operations Command Joint Special Operations University. He holds a B.A. in National Defense Studies from Kings College London and is a graduate of the British Joint Staff College.

LTC Marius Kristiansen is an active duty Norwegian Army Officer. LTC Kristiansen currently serves as the Norwegian Exchange Officer in the U.S. Special Operations Command Headquarters J3-International Division. He holds a B.A. in Military Leadership and Land Warfare from the Norwegian Military Academy, an Advanced Certificate in Terrorism studies from the University of St. Andrews in the U.K., an M.S. in Defense Analysis from the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, and is a graduate of U.S. Marine Corps Command and Staff College.

Disclaimer: The views presented are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Department of Defense, the U.S. Special Operations Command or the Norwegian Armed Forces.

References:

[i] Norwegian Intelligence Service (NIS). Fokus 2021, p. 46. https://www.forsvaret.no/aktuelt-og-presse/publikasjoner/fokus/rapporter/Fokus2021-web.pdf/_/attachment/inline/b9d52b53-0abe-4d1c-9c51-bf95796560bf:8dd66029b7efb38aab37d13e8b387d2e6ed0bd05/Fokus2021-web.pdf

[ii] Regaining Arctic Dominance – The U.S. Army in the Arctic, Department of the Army, 2021. https://www.army.mil/e2/downloads/rv7/about/2021_army_arctic_strategy.pdf