In 2011 the war in Afghanistan was racing full tempo on the back of both president Obamas surge of troops on 2010 and the concept of population-centric comprehensive counter-insurgency. In the city of Gereshk, district of Nahr-E Saraj, Helmand province, southern Afghanistan, the coalition was struggling to curb the insurgents all around the city. It was a situation as complex as ever, with many actors, agendas and attacks. The ISAF forces were all part of the mix, and grasping to understand the nature of the insurgency, in order to win. Suddenly roadside IED’s appeared inside the city targeting the Afghan Police, something new. The US Marines wants to intervene militarily in the city, but was the real reason for the IED’s? In complex environments, the usual intelligence analysis and products did not provide the international forces with the necessary understanding of the operating environment for them to have an advantage over partners and adversaries. Despite the assets of human intelligence and electronic warfare, the intelligence was fragmented and flawed. Intelligence needed to provide a much deeper understanding and this was conducted by an unlikely team, who through a tough and thorough analysis shed a much better light on the whole operating environment in Gereshk, providing a foundation for the commanders to better navigate operations and strategy. The solid intelligence product titled Understanding Gereshk set new standards for intelligence analysis at the lowest tactical level, and it provides lessons learned and inspiration for intelligence analysis much beyond Afghanistan.

Part 1: How the counter-insurgencies put new demands on military intelligence doctrine, organization and tasks.

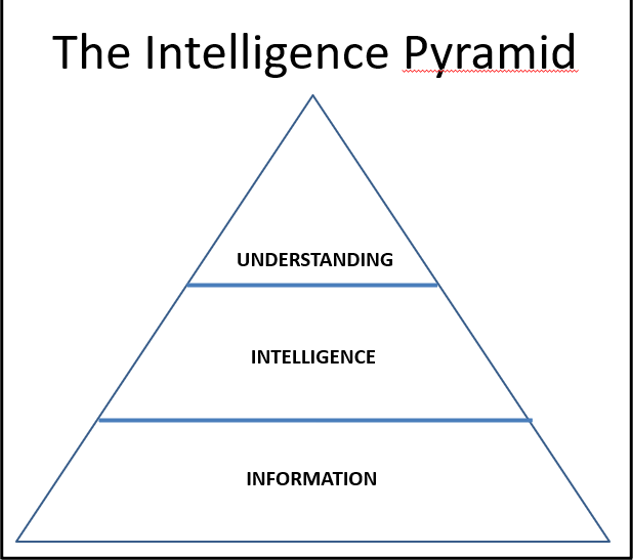

In this article I wish to suggest the use of the term understanding to be operationalized within tactical military intelligence, as part an intelligence pyramid distinguishing between information, intelligence and understanding, with implications for both direction, collection, analysis and distribution. It is based on my own use of the term as the senior analyst with the Danish Army Intelligence Center (AIC) from 2014-2016, which again is based on my experiences from Afghanistan and Helmand the preceding years.

The word understanding is very generic, and while it seems unnecessary to make a case for why an intelligence analyst should understand what he is analyzing, I suggest to incorporate it in actual doctrine and in analysis, at a low tactical level. Understanding as a term is as much product-oriented, and aimed at the intelligence consumer, rather than at the analyst. In this article I will explain how I used it, and how I suggest that it may be used. It is intended as experiences from the field, shared to interested fellow intelligence leaders.

A historian by university education, and only a national guard/reserve officer, I was deployed to Afghanistan in early 2010, as a staff officer within CJ35, Future Operations, of the ISAF Joint Command (IJC) in Kabul. After six month, I deployed to Regional Command South West, led by the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force (1MEF), where I was chief governance planner within the C9, for a further six month. In 2011-2012, I was the Political Advisor in the Nahr-E Saraj District Stabilization team (DST), and mentor to the local governor and his administration.

Throughout this interesting deployment of more than two years, I had several dealings with the intelligence field which shaped my development of the intelligence pyramid, and the coining of the term understanding. I will thus build the article chronologically, with the experiences and inputs from Afghanistan, as they are key to explain the role of the term understanding, and the use of the intelligence pyramid.

The Danish doctrine of military tactical intelligence

The Danish army doctrine for tactical intelligence is a small red book simply called “regulations for tactical intelligence” in free translation, often only known by its acronym “TAK-E”. It is aimed primarily at battalion and brigade level, and nothing really exist to supplement it above this level. Courses are run, to total three weeks, to prepare intelligence non-commissioned officers and officers up to brigade level. It must be added, that Intelligence was not a branch within the Danish army until 2014, so the publication and doctrine was developed and owned by a small team at the Military Academy. The publication is classified as restricted, so it is not possible to summarize it here. However, no secrets are revealed claiming that it does not offer much different than basic intelligence doctrine found in NATO publications, such as ATP-2 and AJP-2. It explains the intelligence cycle, to some extent the intelligence requirement management process, something about named areas of interest on a map, etc. The doctrine does not include things such as a targeting process, neither does it include anything on analytical models in counterinsurgency, such as PMESII or DIME.[1] It did however list the various intelligence products, such as the Intelligence Report and the Intelligence Summary, as templates. As a young officer, encountering this was interesting, but it did not take long to ponder how simple and antiquated it seemed. I feel as if it had not developed since what was necessary for an infantry battalion in 1944.

Counter-Insurgency and the new demands on Intelligence

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan put new demands on traditional intelligence organizations. Far from the strategic intelligence failure of detecting and warning of the 9/11 attack, regular military units found themselves in a foreign society, fighting one or several strange enemies. They ranged from terrorists, criminals, locals defending their village, organized insurgencies, warlords or any combination of these at the same place, and the same time. Intelligence on an enemy is never easy, but the standard military intelligence organization of a western infantry battalion, brigade or division was wholly unprepared and not organized for it.

By 2010 a new concept of intelligence saw the light of day, with major general Michael Flynns famous article: “Fixing Intel – A Blueprint for Making Intelligence Relevant in Afghanistan”.[2] Regardless of what happened later, both to Michael Flynn and the campaign in Afghanistan, and in the intelligence communities, this article and its suggestions were breaking news, and heralded as a solid evolution of the intelligence field. In essence it intended to broaden the focus of the intelligence organization from focusing narrowly on the enemy, to include a whole of society approach. It included fusing all available information from civil affairs and other sources, to build as complete a picture of the operating environment as possible. Underlying these intentions, there no doubt was a realization that the coalition forces were not winning the war by killing insurgents, who more often than not may not have been insurgents. In this sense, it was very much in line with the overarching counter insurgency trends prevailing at the time, notably general McChrystals “Comprehensive COIN”, focusing more on good governance and development, than on killing insurgents. This in turn, was much in line with Kilcullens theses on counter insurgency, and general Petraeus continued this approach in 2010, after taking over from McChrystal. At this time, in late 2009 when the new three-star Headquarters was stood up in Kabul, the intelligence branch of this Headquarters became huge, in order to play the role of a true knowledge base. The HQ functioned along the crossfunctional team approach, a sort of matrix organization which I have described in another article from 2010.[3]

The intel branch of this HQ was named “the information dominance center”, (IDC) as if also to expand from pure intelligence to information in general. The primary tool of the IDC was the so called “Afghan Wiki”. It was in essence modelled after Wikipedia, and its aim was to be an encyclopedia of all data, information and intelligence throughout all of Afghanistan. At the core of the Afghan Wiki was data and information on Afghan officials, for example district governors, council members, mayors, notable tribal elders, history and connection of tribes, data on roads and buildings, etc. It was being built and fed by all IASF units, high to low, as is the real world Wikipedia. Local units would feed data on local governors and warlords into the Wiki, and thus build a complete picture. So called “district assessment teams” would leave Kabul every week, to visit a faraway district and asses it with the local unit, and return with tasks and inputs to orders and briefs. The question is, what this picture was worth, intelligence wise.

This Afghan Wiki was available to us as staff officers throughout the HQ as basis of our planning. Whenever we had operational planning teams and tasks, the contributing Intel Officers, which came out of the IDC, mainly contributed with information from the Afghan Wiki. Almost as lines of operations, the three main focus themes were Governance, Development, and Security, and in that particular order. Every single district in Afghanistan were assessed in this way, by traffic lights, ranging from green if conditions were good, to red if Taleban prevailed or ISAF had not been there yet. It was very deliberate that governance came first, in line with the overarching counterinsurgency doctrine, that the Taleban would not be defeated militarily, but by making the Afghan government a better alternative for the people to choose, and thus to remove their support for the Taleban. It would be superflouos to expand on if this was successful or not. I do feel however, that in 2010 it was a major change that gained traction, that it did in fact help shape the overall fight, both tactically and operationally, in the right direction. Intelligence in the form that Flynn had suggested played a major role in this shift of perception and defacto doctrine. Even with all of this, it still occurred to me, that we sat in a 1500-man headquarters in Kabul, and did not quite know what we were up against.

Gereshk – Bangkok of Afghanistan

After Kabul, I transferred to Regional Command Southwest (RC(SW)), at Camp Leatherneck out in the Helmandi desert. Embedded in the C9 stability of the US Marine Corps Headquarters as the Chief Governance Planner, a senior staff officer appointment, I suddenly had to plan much more for implementation of good (afghan) governance. It often meant service delivery, counter-corruption, educating local officials and staff. Within the headquarters, made up mainly of the 1. Marine Expeditionary Force (1MEF), planning was much more fragmented than in Kabul, and focus was much more on fighting the enemy. It must be added, that Helmand was perhaps the most contested of all Afghan provinces, with most kinetic incidents at the time, so perhaps the focus was understandable. We had some interaction with the intelligence branch of the headquarters, but not to a great extent. We did however interact much with such elements as Female Engagement Teams, CIMIC, the Helmand Provincial Reconstruction Team (H-PRT), Human Terrain Teams, etc. Here, I had to perfom some of the district assessments on governance, and to provide input for the Afghan-Wiki.

Following this, I moved to the District Stabilisation Team (DST) in the district of Nahr-E-Saraj in Helmand, where I would stay for 14 months, and learn what understanding means. Or, to be more precise, what the consequence was of not understanding. In this district I was to be the mentor and political advisor to the local governor, in the sprawling city of Gereshk. I was located with the Danish Battle Group, a battalion sized unit responsible for much of the central district, including the Gereshk city itself. In this battalion headquarters, it was as if they had understood Michael Flynns message, that traditional intelligence was insufficient for counterinsurgency. A normal Danish battalion would have had an intelligence section (S2) of just a couple of people. Now, it was more than 10 people, ranging from specialists, non-commissioned officers and officers. It had a database and mission secret computers. The battalion furthermore had both a large CIMIC-unit as well as a HUMINT team, and powerful electronic warfare units. Even the Danish Defence Intelligence Service had a liaison officer at battalion HQ. Infantry Companies from the British Army, who were in the district, often had a so called “COIST” – Company Intelligence Analyst, to compile and collect all forms of information to feed into the intelligence system. The District Stabilisation Team, abbreviated DST, was a team of civilian stabilization advisors, often 4-8 people, actually working for the Provincial Reconstruction Team, in a parallel chain of command. As civilians, we were supposed to work in coordination with ISAF military units, but not to share intelligence. In fact, several of my colleagues, being civilian advisors, decided actively not to work with intelligence officers, or share information with them.

Despite this plethora of intelligence assets, including more strategic and electronic collection assets, as well as intelligence support from brigade, regional command and other entities, it was still extremely difficult to provide the correct and necessary intelligence. This was irrespective of it being enemy centric, regarding Taleban cells and operations, IED-emplacements, or towards the political and powerbroker networks. It was just as Michael Flynn had described in his article from 2009, that the fight was as much population and society centric, as it was enemy centric, and in this type of fight, higher headquarters intelligence analysis could provide little: the necessary intelligence came from the tactical level, and would often remain there. Gereshk city in particular, but the Nahr-E Saraj district as a whole proved incredibly difficult to understand, and thus to conduct effective counter-insurgency operations in. We simply did not understand the whole operating environment well enough.

Gereshk and Nahr-E Saraj was however also on of the most complicated places in all of Afghanistan. It was a conflux of clans, business, history, war, geography, trade, roads, and much more. The district as well as the city itself straddled the Helmand river, both encompassing green, lush and fertile land near the river, many irrigation ditches and small societies, but also arid and desolate deserts both to the east and west. Just to the south were powerful and rich districts such as Nad-Ali, and to the north some of the most hostile of all places, the upper Gereshk valley, with places such as Sangin, the road to Musa Quala, and other evil places. The Afghan ring road, Highway 1, passed right through Gereshk city, over a couple of absolutely key bridges. The city itself was sprawling, a huge bazar, hospital, schools and many relics from previous development efforts. An old fort from the time of Alexander the Great, or perhaps a bit newer, loomed over the city, and was now the local prison. Traffic was massive and chaotic, and the city full of police checkpoints. Its population was estimated to around one hundred thousand, but it would probably fluctuate. We called the town the Bangkok of Afghanistan, because it was where everyone and everything came together: crime in general, corruption, extortion, opium trade, weapons trade and trafficking, and all the convoys along the highway made a lucrative business for the police to control the checkpoints. Our intelligence estimated that the best checkpoint at the road could make up towards one hundred thousand dollars per day, in bribes from passing convoys, most of them probably ferrying goods for the international forces. Gereshk was serious business. How could this possibly be understood, in military intelligence terms?

We, as the internationals, did not understand, and we made many mistakes. One of the more curious mistakes however, was that we all seemed to think the Afghans themselves understood everything perfectly, and if we could just find that one Afghan who would tell us, it would all be clear. We never grasped, that they themselves just worked with in and lived in it, and perhaps did not fully understand all relations and mechanisms themselves. It is probably very likely that they used us, played us, and often fed us misinformation, incorrect information, or just too much information. How would a military force, with a short timeline and the usual military sense of initiative and lack of patience respond to this? Several examples stand out to me, as relevant to explain the lack of understanding of the operating environment, and the lack of sufficient military intelligence.

The story that best serves to illustrate our lack of understanding, is what I would call “the summer of IED’s”. In the summer of 2011, suddenly roadside IED’s targeting Afghan National Police (ANP) Vehicles began appearing inside the Gereshk City Limits. This was very atypical, as Gereshk city was seen as a place where no fighting took place, and it had been a long time since any IED had been found. Targets were all ANP, but seemed random. They were at varying times, and varying places, but also found along the main highway, were many ISAF vehicles, including my own, often drove. This was a major security concern. Everyone spoke to the ANP and everyone suspected the Taleban; who else would emplace IED’s? The situation was so dire, that the commanding general from the regional command came to visit the local battalion commander, and the two had a fierce encounter. The general wanted to send in two US Marine Corps battalions to establish security and clear the city. The local commander was unto something being amiss, but not exactly what, and resisted. During my conversations with the local governor, I did get a feeling, that it wasn’t the Taleban, but something else, perhaps between major powerbrokers. Without US Marine involvement, and after a couple of weeks, it turned out to be the elders of the city laying the IED’s, to send a stark message to the ANP, that one of their lieutenants were going too far, in terms of bribes and extortion, and using younger girls from the town. When the Chief of Police, who were related to this Lieutenant, fired him and sent him off, the IED’s stopped immediately, never to return again. It was a complete classic of a foreign intervention intelligence failure. Everyone blamed the Taleban, a clear cut case of cognitive closure, and we simply did not have a view on alternate explanations. We simply did not understand the society we were in.

After summer, another bi-annual rotation of the battalion in charge occurred. The incoming unit, in self perception much better than the outgoing, quickly established, that an area to the north of the city was not secured. Too many incidents of shootings and IED’s. It needed to be cleared, as the operational term was. Having been their longer, I now knew, that this occurred every time a new unit came in, and in precisely the same area. Operations would take three weeks, have meager results, and then stalemate and patrol for another 4-5 month, and the next units would come. It was in essence futile repetition, but sadly deadly to soldiers. I tried to explain this as length to the incoming colonel, who for once seemed to understand. Operations were altered, and it made no change whatsoever to the area. We simply did not understand the underlying dynamics.

Another curious example of lack of understanding, was the Hawaladar raid of early 2012. In Gereshk there were many Hawaladars, which in essence served a banking function. The most powerful Hawaladar of Gereshk naturally did business with everyone, including the governor and the Taleban. His business was money, not politics or war. A couple of times, a colonel from the special forces environment had called me up to ask me about this particular Hawaladar, and sometimes the point had come up, what I thought would happen, if he were to be taken in for questioning, as he politely called it. My answer had been clear: nothing. I was sure that business and money streams to and from the Taleban would continue with some other Hawaladar, and nothing be gained. If they wanted intelligence, I suggested that I could plant a microphone in his office, or that they should follow the messengers from the Taleban as they left his office. One morning I was awakened by a furious governor on the phone, and his advisor calling at the camp gate. Mid morning, a handful of pickup trucks with masked men had pulled up at the Hawaladars office, and kidnapped him, and taken one million dollars, in broad daylight. I knew who to call. Answers were not forthcoming, but the following events served to prove that we did not understand what we were doing. Apparently, the Hawaladar also did business for the well connected provincial governor, who were friends with the president in Kabul. A few hours later, while I was with the governor, the president, then Hamid Karzai, called and asked the governor if he was not in control of his city, since ISAF forces could roam in and kidnap businessmen at broad daylight, and threatened to fire him. He was a good governor, whom we very much wanted to keep. Another few hours later, I called on the governors office, and sitting next to the governor in his sofa at the mansion, was the Hawaladar himself. Not until then did I find out, that the special forces had kidnapped the wrong man, the Hawaladars brother, and didn’t even know it. Later on the phone, the colonel from special forces was very silent when I told him that I had just had tea with the intended target. His counterstory, that they had always intended to bring in the brother, sounded less sincere. Of course the special forces did not steal a million dollars from the shop, but people on the street saw sacks of something being hauled into open pickup trucks, so the claim was very difficult to refute. Followingly, it took a couple of month before the brother was released from custody, and apparently had told nothing of value. The books taken were handed back to the governor in a ceremony fit to ridicule ISAF completely, as if we had done the Afghans a favour. We simply did not understand how things were connected and worked.

I have a plethora of examples like the ones above, from just two years of deployment, and it would take far to long to retell all of them. It ranges from wrongly placed schools, corruption in contracting projetc that ISAF held the Afghans from intervening in, to the security infrastructure, to naming of bridges the Afghans didn’t need, and so on. Besides, it should be a believable claim now, that we as western forces, did not understand afghan society sufficiently to conduct the sort of counterinsurgency operations that we did.

FOOTER

[1] I will not elaborate on these models here, but refer readers unfamiliar with them to research it elsewhere.

[2] AfghanIntel_Flynn_Jan2010_code507_voices.pdf (s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com)

[3] Tilbakeblikk: The missing operational level (stratagem.no)

Photo: Defence Imagery UK/Wikimedia commons/An officer from the Royal Ghurkha Rifles (RGR) shadowing his Afghan counterpart prior to entering the village of Saidan near Gereshk, Afghanistan, Oktober 17th 2010.